The Sinking of the Dix

Today, the sinking of the Dix. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

November 17th, 2006: This is the hundredth anniversary of the sinking of the Dix. Not quite up there with the Titanic or the Edmund Fitzgerald, but an event to remember anyway. It was the worst maritime disaster ever suffered in Puget Sound. You might even call it a collision of technologies, although that gets ahead of my story.

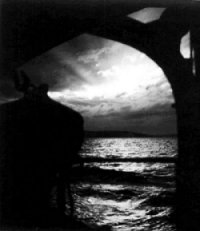

The place is Alki Point -- the furthest western tip of Seattle; the time is 7:00 PM. The Dix is a ferry that carries passengers to and from Port Blakely on the southern end of Bainbridge Island. It is a scene that brings back memories. For I once rode the next generation of ferries across Puget Sound. I know evenings like this was -- cool, clear, and windless, the setting sun making a glorious canvas of the western sky. Evenings when all was right with the world and nothing could go wrong.

The place is Alki Point -- the furthest western tip of Seattle; the time is 7:00 PM. The Dix is a ferry that carries passengers to and from Port Blakely on the southern end of Bainbridge Island. It is a scene that brings back memories. For I once rode the next generation of ferries across Puget Sound. I know evenings like this was -- cool, clear, and windless, the setting sun making a glorious canvas of the western sky. Evenings when all was right with the world and nothing could go wrong.

But, 15 minutes earlier, the Schooner Jeanie had left the downtown Seattle docks and it headed our across Eliot Bay with 400 tons of iron ore in its hold. It was coming around Alki Point. And, as both ships headed southwest, their paths would soon converge.

The Dix was a 130-ton passenger steamer, a hundred feet long. The Jeanie was a large three-masted ship that could run under either stem or sail. She was now running on steam. The Jeanie weighed eight times as much as the Dix.

The Dix was a 130-ton passenger steamer, a hundred feet long. The Jeanie was a large three-masted ship that could run under either stem or sail. She was now running on steam. The Jeanie weighed eight times as much as the Dix.

Still, there should have been no problem on this clear evening. The captain of the Dix had gone below to collect fares while his first mate took the helm. But, as the two ships drew close, the mate's attention must've drifted. He didn't see the schooner until frantically blew its whistle.

Both ships tried to stop, and the mate, for some reason, turned the Dixthe wrong direction. The Dix slid under the Jeanie's bow and would've survived the impact even then. But the Jeanie's bowsprit ran into the Dix's superstructure, tipping her just far enough to swamp the decks on the other side. Water rushed in and, minutes later, the Dix rested on the bottom, 600 feet below.

Thirty-eight passengers, most riding on the upper deck and watching that same sunset that I remember so well, were left bobbing in the water while Jeanie's crew quickly and efficiently fished them out of the drink. The son the Port Blakely postmaster might also have escaped. He was near the companionway, but he helped a 13-year-old girl up the stairs and then could not save himself.

At least 39 others went down with the ship -- maybe as many as 45. This was a Sunday evening and most of the dead had been returning from a day in Seattle to their homes in Port Blakely. It was a horrendous disaster for that little town.

At least 39 others went down with the ship -- maybe as many as 45. This was a Sunday evening and most of the dead had been returning from a day in Seattle to their homes in Port Blakely. It was a horrendous disaster for that little town.

And so, on this hundredth anniversary, the town remembers its loss. Grandchildren of survivors gather for the memorial. This was not the Titanic, of course, but much larger in such a small place.

An old schooner collided with the newest steam passenger boat and left it on the seabed below. And there it is remembered, at least in that corner of America, even today.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

A great deal of material is available on the web. See, e.g.: This extensive historical account.

The image of Dix above is a contemporary photo of the brand new steam ferry. The other two photos were taken at sundown from a Puget Sound sound ferry by P. P. Roy Choudhury in 1952.