Sacred Site or Theme Park?

by Rob Zaretsky

Today, historian Rob Zaretsky asks, is it a sacred site or a theme park? The University of Houston presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Build it and they will come. Be they secular or religious pilgrims, they will come by the millions. They will come with similar desires, and will be welcomed in similar ways, though the ends seem dramatically different: salvation on the one hand, entertainment on the other.

These, at least, were my thoughts as my family and I were carried by a wave of humanity toward the gates of Disneyworld. The air crackled with excitement, while the faces wore blissful smiles. This was no less true for senior citizens than for children. As these elderly folk, many in wheelchairs and others with walkers or canes, made their way to Main Street USA, they were welcomed by the voice of Jiminy Cricket. We had all reached the Magic Kingdom: the place, according to Jiminy, where dreams come true.

Forty years ago, Orlando was an unlikely place for such promises. Swampy and mosquito-infested, this brackish backwater was well off the beaten tourist trail. Then Walt Disney had a vision -- Tinkerbell descending from the heavens -- and he built his kingdom. The infrastructure followed: highways, monorails, airports, sewers and power plants. In quick succession, there came competing kingdoms -- some boasting animals, others movie stars -- and, of course, the countless hotels and restaurants and souvenir emporiums to service the rising tide of pilgrims.

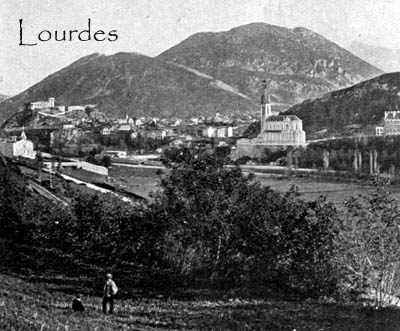

This same outline applies to Europe's most famous pilgrimage site, Lourdes in southern France. There, in 1858, a young girl, Bernadette Soubirous, saw a vision of the Virgin Mary. By the end of the century, this sleepy provincial town had become a bustling city, built quite literally on the underground stream that had been discovered by Bernadette. Lourdes soon sagged under a major railway station, funicular, and jammed boulevards lined with hotels, restaurants and souvenir emporiums. Even then, the city could barely service the more than one million pilgrims who, in 1908, descended upon it.

And they came, and still come, with the hope that, by bathing and drinking at the grotto, they would leave without their wheelchairs and canes. And with, at the same time, their porcelain statuettes, postcards and even pastilles de Lourdes -- lozenges made from the water of the grotto. The promised health benefits were otherworldly.

Perhaps the true miracle resides in the way that modern commerce and devotional practice blended to create this modern shrine. As Suzanne Kaufman has pointed out, the genius of the local religious and civic leaders was that they taught traditional pilgrims to act like modern tourists. In Lourdes, they not only paid reverence to the grotto -- but they also paid billions of francs to visit the dioramas and wax museums recreating Bernadette's experience, as well as to buy the bric-a-brac bursting from every store.

One outraged Catholic, J.K. Huysmans, dismissed Lourdes at the turn of the century as the capital of "American abominations." How ironic. After all, Disney created a perfect mirror of Lourdes: modern tourists are now pilgrims to their lost childhoods. At the Magic Kingdom they seem to hear once again intimations of their own immortality.

I'm Rob Zaretsky, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

S. K. Kaufman, Consuming Visions: Mass Culture and the Lourdes Shrine. (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2005).

All images are from John L. Stoddard's Lectures, Vol. V, (Boston: Balch Brothers Co, 1898/1903).