Glass and Bottles

Today, America makes bottles. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

In 1608, the year after they'd reached Jamestown, settlers tried to start, of all things, a glass factory. They attracted several European settlers who knew that trade. Their attempt lasted only about six months, but archaeologists have excavated glass fragments and one complete glass bottle from that period.

Thirteen years later, Jamestown tried again. This time, they imported four Italian glassmakers. They managed to produce drinking glasses and some window glass, as well as bottles.

By 1639, the new Plymouth colony had set up a glassworks. Philadelphia was in the business in 1683. And so it went; 1813 found Pittsburgh -- still an outpost, separated from most of America by the Appalachians -- with five glass factories.

One might wonder why all this attention to a nicety like glassware, while starvation still lurked outside the door. We forget that our first settlers were Europeans accustomed to some level of finery. They expected to quickly recreate their old life in this New Jerusalem. They had no thought of starting from scratch, and ultimately had a very hard time of it. Many were quite unaccustomed to the hard manual labor of bare subsistence.

All this came into focus for me when I found a 1920 book on American bottles. It's a catalogue of the private collection of an Owens Bottle Company executive. The older bottles in his collection were from the early 19th century, and most had short necks with rounded bodies. Most were green, amber or blue depending on the impurities in the glass. Most important, all were essentially handmade, with fancy decorations molded into the glass.

You see American eagles, busts of Washington and fancy designs. Here an amber flask with the Ben Franklin's face, there, green bottles imprinted with Jennie Lind or a cornucopia.

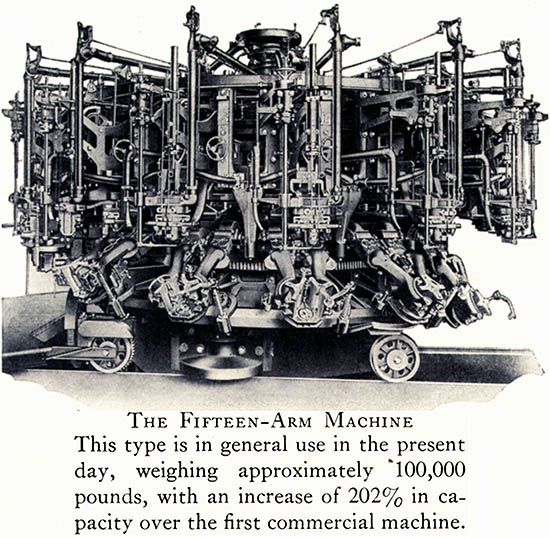

Owens Glass began experimenting with bottle-making machines in 1899. They improved their way through several models. And, by 1906, bottles everywhere were being made by robots -- bottle-making machines. With them came a profound change in the very meaning of the word bottle.

Owens Glass began experimenting with bottle-making machines in 1899. They improved their way through several models. And, by 1906, bottles everywhere were being made by robots -- bottle-making machines. With them came a profound change in the very meaning of the word bottle.

Their costs had been reduced, overnight, "to a vanishing point," as one industry commentator put it. Now bottles began displacing even tin cans. And, in this economy of cheap disposable containers, the frills vanished as well. The plain milk bottle and the long-neck beer or soft-drink bottle appeared. Coca Cola was the old-timer among bottled soft drinks. Founded in 1886, it kept its old-time fancy molded flasks.

But elsewhere, plain glass bottles took its place. For a season, the cheap bottle would be a staple of the American scene. Today, paper and aluminum have moved in to displace glass. But remember, next time you open one of the surviving glass bottles, that you are carrying on a tradition as old as the first Virginia Colony.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

W. S. Walbridge, American Bottles Old & New. (Toledo: The Owens Bottle Co., 1920). (Images below are from this source.)

Here are some web sources on early Colonial glassmaking:

http://www.historicjamestowne.org/featured_find/wine_bottle.php

http://www.historicjamestowne.org/