Earth Abides

Today, Earth Abides. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Let's talk about the apocalypse; for Earth is under threat. A century hence, things will be very different. They could well be worse. We're threatened by overpopulation and global climate change. Some believe that our vulnerabilities to poverty, disease, and natural disaster are rising faster than technology can respond. Where do you suppose we're really headed?

Consider scenarios. Best case: technology, combined with common sense, will rise to the challenge and save us -- as it's so often done. Worst case: Earth's climate will deteriorate enough to eliminate humankind entirely. Or a huge portion of Earth's population could die of war, disease, and starvation, before a new civilization rises from our ashes. That happened six centuries ago, when famine, followed by plague, wiped out much Earth's population.

In the years just following Hiroshima and Nagasaki, science fiction gravitated toward apocalyptic themes. So many last-people-on-Earth stories -- humankind reduced to a few survivors, tribes warring over the last tins of canned food, that sort of thing.

It was all a bit over the top. But one book offered a version that showed surprising wisdom. The hero of George Stewart's 1949 book Earth Abides is geologist Ish Williams. Ish is in a protected mountain spot when plague wipes out Earth's population. (The name Ish derived from the famed Ishi, last of the extinct Yahi Indians.)

It was all a bit over the top. But one book offered a version that showed surprising wisdom. The hero of George Stewart's 1949 book Earth Abides is geologist Ish Williams. Ish is in a protected mountain spot when plague wipes out Earth's population. (The name Ish derived from the famed Ishi, last of the extinct Yahi Indians.)

At first, Ish seems to be the only living human. Then others appear. He meets a woman, Em, and they mate. They raise children and form a small community. At first Ish tries to keep education alive. But the forces of nature gradually destroy the libraries, and disease kills their one son who has a talent for reading and an interest in preserving knowledge of the past.

Time goes on. One day, out of the blue, it dawns on Ish that Em is a light-skinned Afro-American. That was so irrelevant that he just hadn't noticed before. (Remember, interracial marriage was still illegal in many states when the book was written.)

At the end, as an aged Ish talks with one of his many great-grandchildren, he ponders his and Em's attempt at restarting the human race. For this lad is a skilled young Paleolithic hunter-gatherer. Ish's line no longer reads, writes, or forges metal. They have bows, arrows, and primary tools. This, then, is the point from which humanity will have make its fresh start.

While I don't look for Stewart's apocalypse, he certainly saw how technology works -- the need for critical mass and infrastructure. We'd begin again, but not with books and engines.

He also gave his book a wise title, Earth Abides. When things get very bad, we humans, we makers of machines and solvers of problems, will retrench. We still hold in our hands the means for our survival. We may be foolish enough to ignore those means much longer than we should. But I doubt that we're foolish enough to exterminate ourselves entirely.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

G. R. Stewart, Earth Abides. (New York: Fawcett, 1986/1949).l

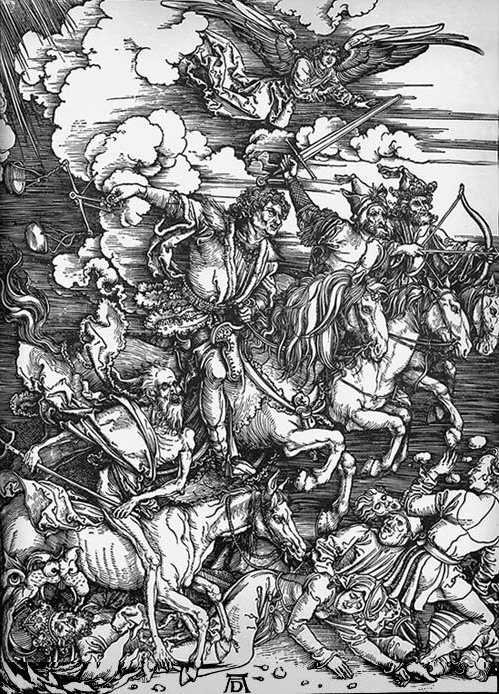

Albrecht Dürer's Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse