Tenement Houses

Today, we look for affordable housing. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Some of you may've seen the movie Gangs of New York, about the horrible life of Irish immigrants in Manhattan's lower East Side before the Civil War. The movie was about how gang warfare was bred in the appalling living conditions of those slums, but it also suggested something of the horror of the living conditions themselves.

Much of that housing could be described by the general term tenement,which meant any multiple family dwelling. After the Civil War, the slum-landlord owners of the tenements had let conditions get bad enough that New York finally undertook reforms.

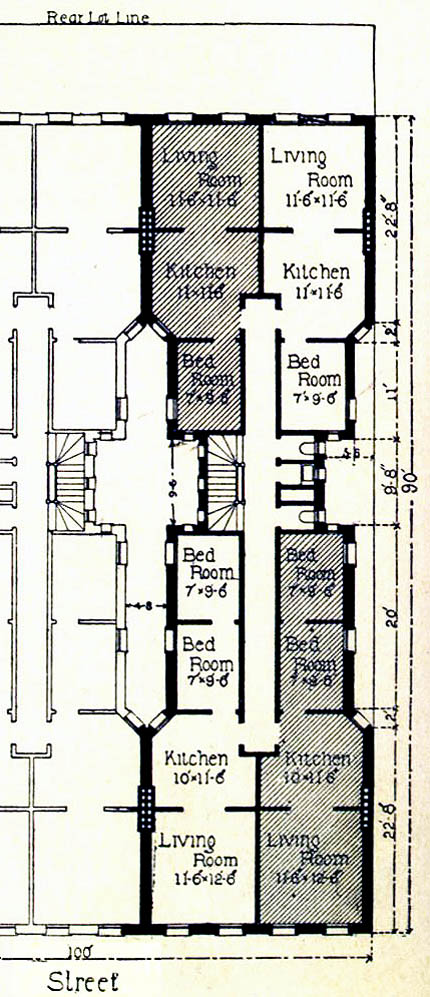

The result was a more-or-less standard tenement house, and it was a huge improvement. The new regulations had called for things like windows and ventilation shafts. I learned how those would-be model homes were laid out when I thumbed through the 1894 Scribner's Magazine. An article by noted architect Ernest Flagg, The New York Tenement-House Evil and Its Cure, showed standard tenement floor plans, and Flagg began with the words

The greatest evil which ever befell New York City was the division of the blocks into lots of 25x100 feet.

Tenements were now designed as modules, each of which occupied one of these lots, edge-to-edge, except for a ten-foot yard in back. A tenement house was a four or five storey row of modules. So let's look at the floor plan in a module:

The 25-by-90 strip was split down the middle and cut in two to make apartments for four families. The ones in front had two bedrooms, a kitchen and a living room -- twelve feet wide and forty feet long. The units in back were similar, with only one bedroom. The bigger ones were just over 400 square feet, the smaller, around 340. Four families shared two toilets and a sink in the hallway.

Regulations now required a two-by-forty-foot notch in each side of the module. When modules were placed together, this created a four-foot wide shaft into which the kitchens vented and a tiny bit of light found its way. Regulations also required windows for ventilation, so your bedroom window was four feet from your neighbor's in the next module.

The logic of these buildings was clear enough, but you can imagine the horrors they'd bred after a generation. They were dark, dank, overcrowded fire and disease traps. Flagg bolstered his cry for new reforms, by suggesting more irregular designs with open courtyards, and greater access to light.

The late-19th-century social reformer, Jacob Riis, also wrote passionately and effectively about housing reform. So better tenements did appear. Today's sprawling New York housing projects are a mid-20th-century solution to the same miserable problem of fitting objects into a box. Still, we need to remember that poverty and crowding, as much as architecture, is the villain that haunts all large cities. Make no mistake, it is a terrible thing to be called into the ranks of the urban poor.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

E. Flagg, The New York Tenement-House Evil and Its Cure. Scribner's Magazine, July, 1894, pp. 108-117. This is the source of the module floor plan below.

J. A. Riis, How the Other Half Lives: Studies among the Tenements of New York. Ed. Sam bass Warner, Jr. (Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard Univ. Press, 1970/1890).

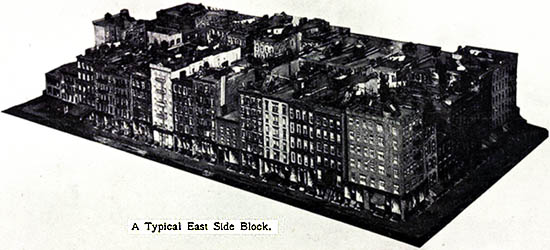

J. A. Riis, The Battle with the Slum. (New York: the Macmillan Co., 1902). The East Side block image below is from this source.

See also, The Lower East Side Tenement Museum: http://www.tenement.org/

I am grateful to Margaret Culbertson, Head Librarian, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, for her significant counsel.