The Industrial Arts

Today, we remember the industrial arts. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

The industrial arts seem to've come and gone. They once represented the oddest segue between two worlds. I've just found a 1922 book that beautifully sets forth its contradictions: Winslow's Elementary Industrial Arts, meant for students in what we now call middle school. This educational form arose after people saw the beauty of manual traditions slipping away in a machine-built world.

Russia, then Sweden, created industrial arts education programs in the 1870s. We began our first one in 1880. All this was fueled by the Arts and Crafts movement, which urged us to reclaim the vanishing manual arts -- to make our own stuff once again. It was regressive; it certainly didn't want to see anything industrial in its crafts. Yet we forget at our peril that any industry rests upon the arts of making things.

Industrialization needed a design focus that the Arts and Crafts ideals unwittingly provided. A movement meant to escape industrialization would now feed it. Instead of replacing industrialization, the ideals of craftsmanship would now serve it.

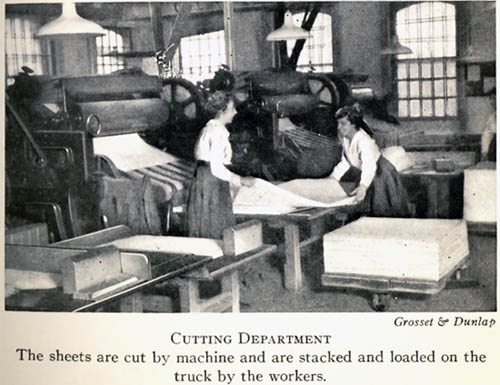

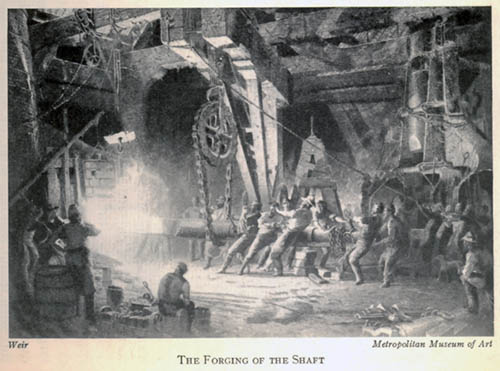

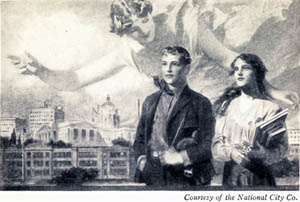

That dynamic becomes very clear as we turn pages of this book, which appeared much later in the game. The very first illustration shows a fresh-faced young man and woman with factories behind them. The book uses photos to dramatize factories and production before it gets down to teaching the arts themselves.

That dynamic becomes very clear as we turn pages of this book, which appeared much later in the game. The very first illustration shows a fresh-faced young man and woman with factories behind them. The book uses photos to dramatize factories and production before it gets down to teaching the arts themselves.

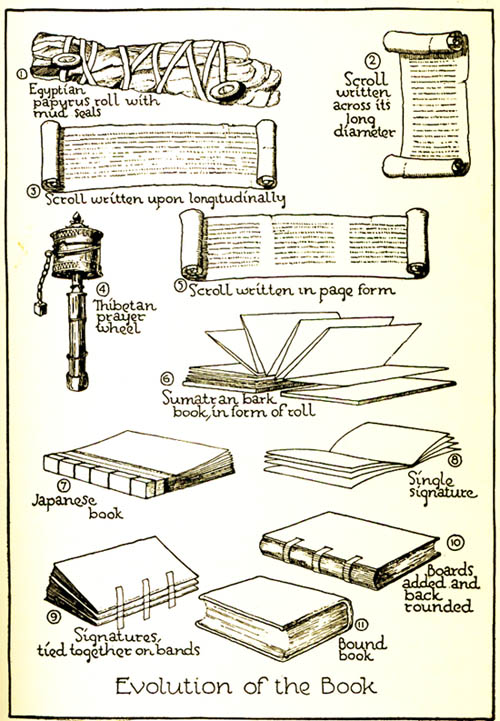

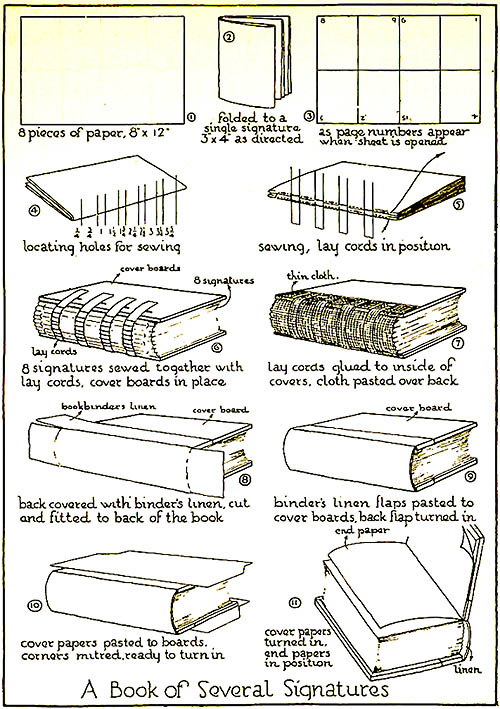

The first two chapters are about book and paper-making. Sure, many photos show how factories made paper and books in the early 20th century. But when the book gets around to actual exercises, it offers crafts that were honed in the Renaissance. Not only here, but throughout the Arts and Crafts movement, fifteenth-century bookmaking sits at the head of the table.

The next chapter, on basket weaving, offers no industrial kinship at all. It's a return, not to the Renaissance, but to prehistory. That's followed by brick-making -- a craft developed in ancient Rome -- and the Neolithic technology of pottery. The chapter on textiles once again shows a few factories: but the focus is on weaving crafts from at least eight thousand years ago.

The nostalgia of the Arts and Crafts movement is clearly alive and well in a book openly fostering industrialization. That might seem to be a glaring contradiction. Yet, for two generations, our industries were fueled by people in contact with the old cottage arts. When I was young, my city (in fact every major city) had a vocational high school which also offered strong academics.

So I finish with the chapter on glass. It describes Venetian glass, stained glass -- as well as huge factory crucibles where modern window glass is made. How completely the 19th-century, back-to-nature Arts-and-Crafts Movement backfired! And, oh, how our schools, which have so abdicated shop, music and art, could use some of that not-so-regressive influence again today.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

L. R. Winslow, Elementary Industrial Arts. (New York: The Macmillan Co., 1922).

Readers might also be interested with the way in which, in 1914, Thorstein Veblen wrestled with theoretical issues that then appeared to underlie the contradictions of art and industry. T. Veblen, The Instinct of Workmanship: and the State of the Industrial Arts. (New York: Augustus M. Kelley, 1964/1914). All images from this source.