A Barrel of Oil

Today, oil by the barrel. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

This summer of 2006, all America watches the spiraling cost of a barrel of oil. As we burn the stuff faster and faster, it grows more precious, and the world warms to its frenzied consumption. But to see the oil barrel as an artifact, rather than an emblem of our troubled times, let's read Robert Hardwicke's 1958 book The Oilman's Barrel.

This summer of 2006, all America watches the spiraling cost of a barrel of oil. As we burn the stuff faster and faster, it grows more precious, and the world warms to its frenzied consumption. But to see the oil barrel as an artifact, rather than an emblem of our troubled times, let's read Robert Hardwicke's 1958 book The Oilman's Barrel.

The wooden barrel was a 3rd-century Roman invention and he shows how the word barrel became a unit of measure. But, alas, the history of units is a terrible morass. Measures of weights and volumes, for example, are constantly confused with one another, since so many things weigh very nearly the same as water. The gallon was defined in medieval times so it would represent over sixty thousand grains of wheat. That would be a unit of weight, not volume. By various accidents of history, the gallon eventually came to be defined as a volume, however. The American and British gallons are 231, and 277, cubic inches.

Containers for practical commerce had to be much larger than a gallon, so barrels had long since been developed, and they eventually took six basic sizes: the firkin, the kilderkin, the barrel, the hogshead, the butt, and the tun (spelled t-U-n). The size of each varies somewhat. They were defined slightly differently for wine, beer, grain, and so forth, and definitions changed from country to country. But a firkin is typically nine gallons and the tun is 252 gallons. That means that a tun filled with water is very close to 2000 pounds -- hence our term ton (spelled t-O-n.)

Containers for practical commerce had to be much larger than a gallon, so barrels had long since been developed, and they eventually took six basic sizes: the firkin, the kilderkin, the barrel, the hogshead, the butt, and the tun (spelled t-U-n). The size of each varies somewhat. They were defined slightly differently for wine, beer, grain, and so forth, and definitions changed from country to country. But a firkin is typically nine gallons and the tun is 252 gallons. That means that a tun filled with water is very close to 2000 pounds -- hence our term ton (spelled t-O-n.)

The beer barrel held 42 US gallons, and they were first used to ship oil in the 19th century. That's still the size we refer to when we speak of a barrel of oil. Yet, if oil should happen to be moved in a unit container today, it'll be a 55-gallon steel drum, with a capacity nearer that of a hogshead than a barrel.

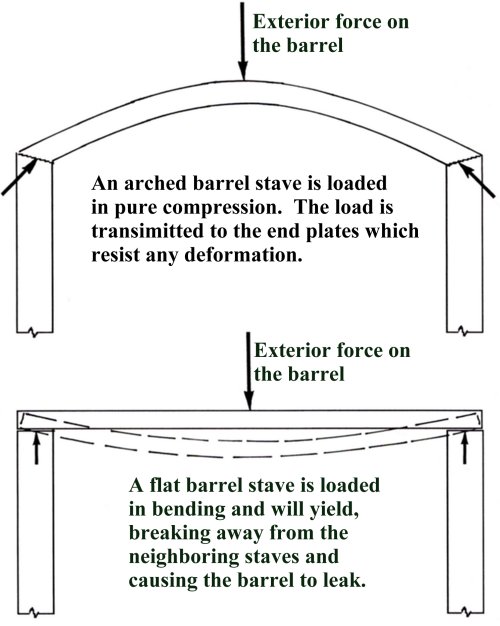

Wooden barrels were marvels of engineering design. Their staves cannot be allowed to bend, so they're given an outward arch. The staves act like stone arches when you press on their sides. Instead of bending, they stay rigid and transmit the force onto solid top and bottom plates. They let one roll a weight that one could never lift. And, since the barrel meets the floor only at one point, it's easy to steer it as it rolls.

In their time, barrels were used to hold everything -- meat, gunpowder, spirits -- even people going over Niagara Falls and living to tell of it. As the death toll among builders of the Panama Canal grew, the companies began using barrels to ship the cadavers back to medical schools in the US.

Now their main use is to store wine, beer, and liquor. Bourbon is cured in charred oaken barrels where a chemical process releases sugar from the oak, and adds a slight natural caramel flavor. But the place barrels really survive is in the abstract digital accounting of our vast consumption of oil -- even though crude oil never touches wood on its long road to our hungry gas tanks.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

R. E. Hardwicke, The Oilman's Barrel. (Norman, OK: Univ. of Oklahoma Press, 1958).

Thirty-two grains of wheat makes a pence, twenty pence makes an ounce, 12 ounces, a pound and eight pounds makes a gallon. That's 61,440 grains of wheat adds up to a gallon of wheat. (And we know that a gallon of wheat will weigh a lot less than a gallon of water.)

Here's a useful online history of barrels, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Barrel

And here's a page on British Imperial units which differ from ours, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Imperial_unit

See also, W. Curtis, The Brilliance of the Barrel. Invention & Technology, Vol 21, No. 4, Spring, 2006, pp. 36-43. (My thanks to Pat Bozeman, UH Libraries, for suggesting an episode from this source.)

A machine for shaping the metal hoops that hold a barrel together, 1892 Appleton Cyclopaedia of Applied Mechanics