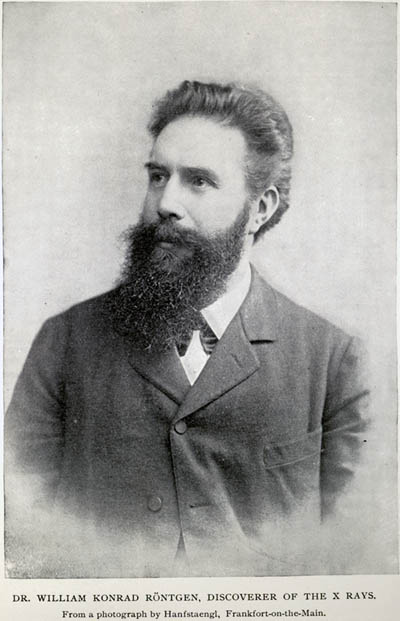

Röntgen in 1896

Today, Röntgen's rays. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

I love one line from the musical Fantastiks. The narrator starts the story, saying, "You wonder how these things begin." Then he spins a yarn much larger than the real lives of his characters. He reminds us that most things have two beginnings -- the cold factual sequence, and the story woven around the facts.

Both beginnings are important: the first, because truth unadorned keeps us honest; the other because how we tell what happened, inaccurate though it might be, very often reveals the truth about us who embrace the story.

Now, a strange case where the two versions almost converged: On November 8, 1895, Röntgen was working in Strasburg with a Crookes tube. He built a cardboard light seal around it and turned it on. He'd meant to activate a fluorescent screen with it, but found he was illuminating a nearby bench through the cardboard.

Something similar had been done by people in Pennsylvania two years before, but they didn't realize what they had. Röntgen did. He worked like a demon to get a paper out in late December. Since he didn't know what to call the illumination, he titled it, On a New Kind of X-Rays.

Three months later, the April copy of McClure's Magazine included an article: The New Marvel in Photography.

In all the history of scientific discovery [it says] there has never been [so] dramatic an effect wrought on the scientific centres ... as has followed, in the past four weeks, upon an announcement [by] William Conrad Röntgen [who] discovered a new kind of light, which penetrated and photographed through everything.

And the legend takes shape. The author goes on to suggest that, by the time this article appears, American labs and lecture halls will buzz with, a "contagious arousal of interest over a discovery so strange that its importance cannot be measured [or] its utility even prophesied." Röntgen struggled to keep his eye on his work in a world delirious with its new X-Rays.

And the legend takes shape. The author goes on to suggest that, by the time this article appears, American labs and lecture halls will buzz with, a "contagious arousal of interest over a discovery so strange that its importance cannot be measured [or] its utility even prophesied." Röntgen struggled to keep his eye on his work in a world delirious with its new X-Rays.

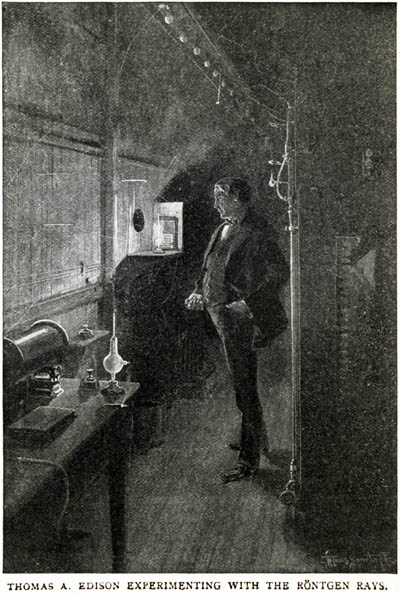

He didn't understand the rays, or even know if they were a form of electricity. "I am not a prophet," he cried, "I am opposed to prophesying. I pursue my investigations." But everyone else went quite mad with X-Rays. They'd already been used to locate foreign objects in ailing bodies and to identify tuberculosis. Edison wanted to X-Ray the human brain. Surely there could be no limit to their efficacy.

Röntgen insisted on the term X-Rays instead of Röntgen rays. But, in 2004, the new element Röntgenium was named after him. He also got the first physics Nobel Prize for his discovery. And, it turns out, he had family in Iowa and wanted to move to America. He would've accepted a job at Columbia University if WW-I hadn't begun. He died of cancer at 78, but probably not from his experiments. He was that rare X-Ray pioneer who shielded himself.

But that was Röntgen, level-headed in the face of all the hoopla -- someone who steadfastly struggled to keep the sane facts of his own life from being rendered on the gaudy canvas of legend.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

H. J. W. Dam, The New Marvel in Photography. McClure's Magazine,Vol. VI, No. 5, Apr., 1896, pp. 401-415. See also following Dam's article in that issue, C. Moffett, The Röntgen Rays in America, pp. 415-420. The text only (no images) of these articles may be get from Project Gutenberg: http://www.gutenberg.org/etext/14663

The image above and the two below are from the McClure's article.