de Havilland and the BE-2

Today, a flying progenitor. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

I'm drawn to pictures; and one book of pictures has been on my mind -- a pictorial history of the 1911 BE2 aeroplane. It's a remarkable old flying machine from a remarkable designer -- Geoffrey de Havilland. Forty-five years after he gave us the primordial BE2, de Havilland was still at it. It was he who made the first jet liner, the Comet.

Still, I can't take my eyes off these pictures of his first aeroplane. And, I've just tumbled to the fact that de Havilland was Joan Fontaine's and Olivia de Havilland's first cousin. I watched their moving-picture images when I was ten, and now I'm hypnotized by this old airplane. Beauty is beauty, I guess.

Geoffrey de Havilland was a 29-year old engineer at His Majesty's Balloon Factory when the War Office realized it needed to pay attention to heavier-than-air flight. So they found a wrecked Voison aeroplane, and asked de Havilland to rebuild it.

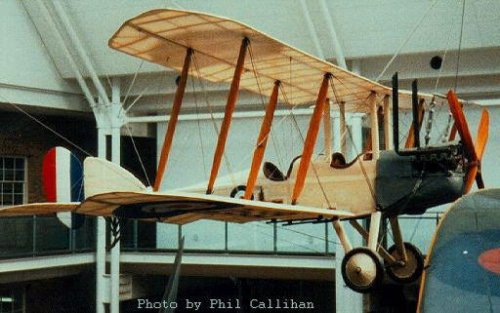

De Havilland saw that he could use its pieces to create his own flying machine. The result was a rangy stork of a biplane -- long slender body, two large wings set far apart, four-bladed propeller, double cockpit, and a long-legged landing gear. He'd never seen a plane in flight, and this had an unhurried aristocratic grace and elegance. Gone was the box-kite look of the first planes. And this was unnaturally quiet in flight. Here, de Havilland introduced the shape and form most light aircraft would keep for the next twenty years. This would be the future.

De Havilland named it BE1 to honor French aerial pioneer Louis Bleriot. It flew only 59 miles an hour. But he quickly made the much superior production model, the BE2, which went through a series of improvements. BE2s served all through WW-I, first as scout planes, then as light bombers, and for defense against dirigibles.

They never could compete with real fighter planes, and were finally relegated to flight training. Their legacy was more genetic in character. You can see BE lines in later military planes -- the SE5 and DH-4. The DH-4 was a design that America adapted for production. Too large for combat, it served as one of our first mail planes after the war.

One lovely heritor of de Havilland's BE2 was his series of Moth airplanes -- the Tiger Moth, the Gypsy Moth, and others. Those light planes served all over the world after WW-I. Beryl Markham flew them in Africa, and you've seen them in countless movies that touch on flight in the 1920s and '30s. Remember the Tiger Moth that began and ended The English Patient?

Our Lone Star Flight Museum recently acquired a Tiger Moth. That lovely buoyant little yellow-painted airplane sits peacefully off among the large WW-II combat planes. And I always seek it out when I'm there. I love its clean efficient lines. All de Havilland's airplanes had a natural artistry to them; and here, in the BE2, we find the taproot of that balance -- way back in 1911.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

P. Cooksley, BE2 in Action. (color by Don Greer, Illustrations by Joe Sewell) (Carrollton, TX: Squadron/Signal Pubs., Inc., 1992), No. 123.

For more on de Havilland and his BE-series airplanes, see:

http://www.ctie.monash.edu.au/hargrave/de_havilland.html

A BE2c, ca. 1915, (courtesy of the RAF Waddington Air Museum )

Tiger Moth, from sometime after 1931, Lone Star Flight Museum, Galveston, TX (Photo by JHL)