Nathan Read

Today, a life well lived. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Nathan Read was a brilliant Colonial American original. When he died at ninety, in 1849, he'd been a Congressman, a gentleman farmer, a teacher of Classics and Hebrew, a druggist, an iron manufacturer -- all that. But his legacy lay in his inventions.

He was a young Harvard student when the Revolutionary War began. When it ended, he was given a teaching post at Harvard. Four years later, the restless Read quit to study medicine. But then, he left medicine to open an apothecary shop.

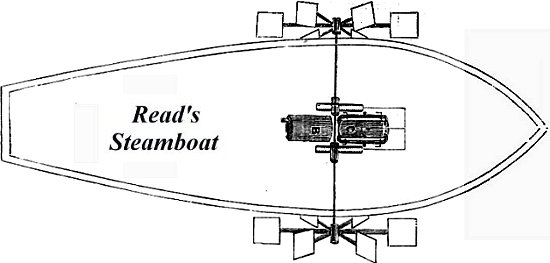

By now our new nation was struggling to create a technological base, apart from Great Britain, and several Americans were trying to invent workable steamboats. Read saw that as the way of the future -- the way of his future.

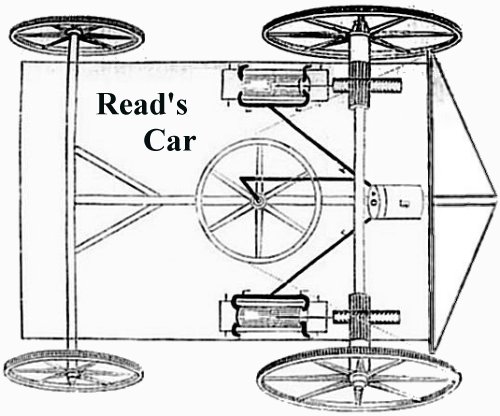

When our patent office opened in 1790, Read was near the head of the line. He submitted both a steamboat and a steam car. Congress ridiculed the steam car, so he withdrew his application. (So much for what would've been the first automobile patent.)

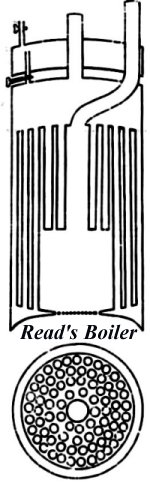

Nathan Read realized that, if boilers were to be small enough to ride in vehicles, a large boiling surface had to be fit in a small place. To replace the old haystacks, he invented a boiler with the fire inside it. Water passed through the fire in tubes. After Read, vehicular boilers all used either water in tubes passing through fire, or fire in tubes passing through water.

Nathan Read realized that, if boilers were to be small enough to ride in vehicles, a large boiling surface had to be fit in a small place. To replace the old haystacks, he invented a boiler with the fire inside it. Water passed through the fire in tubes. After Read, vehicular boilers all used either water in tubes passing through fire, or fire in tubes passing through water.

But he went back and refined his steam boat ideas. A year later, he held a patent for three steamboat components: a double-acting engine, a chain drive to re-place paddlewheels and, most important, a compact tubular boiler. The big low-pressure British steam engines were supplied by so-called haystack boilers -- huge haystack-shaped pots with fires under them.

He failed to get funding to build a steamboat, but he stayed in motion. He turned to manufacturing iron goods. He made cables, anchors and other items for sailing ships. He invented a machine that cut iron strips into the right length for nails, then swaged a head and a point on the ends. In the forests of America, we built of wood. And Read radically sped the needed production of nails.

When he was 48, he moved to a large farm in Maine where he spent the rest of his life. He served as a chief judge of his county court. And he was first appointed, then elected, to terms in Congress. He founded a teaching academy.

And he kept inventing -- a windmill controller, a tidal energy system, a threshing machine, a coffee huller, and so much more. He invented a system that used the expansion of metals under varying temperatures to make a self-winding clock. His creative output was inexorable as sunup. Early America was built so rapidly and so well because it had people like Nathan Read.

His was a life well-lived just because it was a life filled with restlessness, variability, and vision. His inventions have mutated in form, but they serve us still -- two centuries later.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

See entries under Read, Nathan, in the Cyclopaedia of American Biographyand the National Cyclopaedia of American Biography. For more on modern compact tubular heat exchangers, see A Heat Transfer Textbook, Chapter 3. (Available as a free download.)

D. Read, Nathan Read: His invention of the Multibular Boiler and Portable High-pressure Engine, ... etc. (New York: Houghton and Co., 1860/1870)

For more on Read and the race to invent the steamboat, see: A. Sutcliffe, Steam: The Untold Story of America's First Great Invention. (New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2004): Chapter 8. (I am grateful to Andrea Sutcliffe for suggesting Nathan Read as a topic, and for her considerable counsel.