Edward Youmans

Today, education in the outback. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Edward Youmans was born on a New York farm in 1821. (In those days almost all Americans were from farms.) Youmans was precocious. He finished only elementary school, but then systematically educated himself. He was drawn both to the classics and to science; and he taught for a while in a country school.

He was 30 when his first book was published -- a terse, clear Classbook of Chemistry that ultimately sold 144,000 copies. By then, he was also educating his 13-year-old brother William who went on to England to finish his studies with Thomas Huxley.

He was 30 when his first book was published -- a terse, clear Classbook of Chemistry that ultimately sold 144,000 copies. By then, he was also educating his 13-year-old brother William who went on to England to finish his studies with Thomas Huxley.

Edward became a popular lecturer and writer and brother William became an important American science editor. Both served education and their importance becomes clearer when we remember that mid-19th century America was educated more by our production of cheap books, than by schools. Both brothers understood self-education and both worked hand-in-glove with the Appleton publishing house -- a great provider of fine affordable text material.

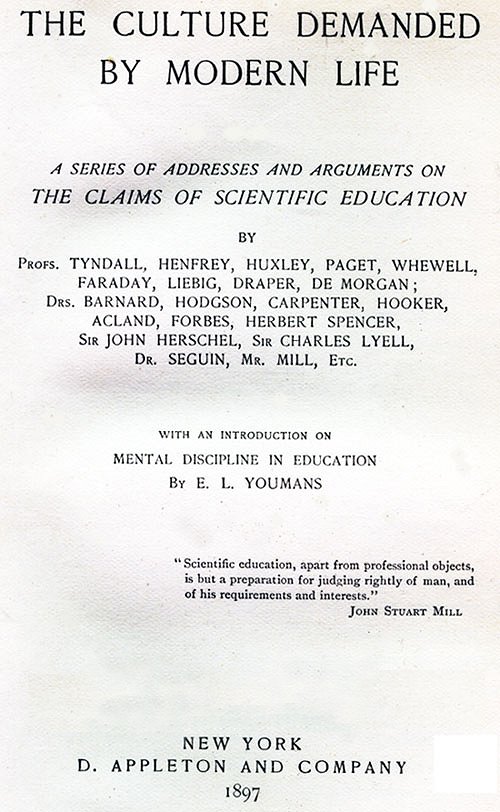

I'd known of Edward Youmans, but I hadn't tumbled to his importance until I found a dusty edition of his 1867 book, The Culture Demanded by Modern Life. He wrote an introductory essay on "Mental Discipline in Education," then gathered a gold-plated A-list of mostly-European luminaries. They all stress the need for disciplined learning in their new industrial age.

British scientist Huxley writes that, "to a clear eye the smallest fact is a window through which the Infinite may be seen." And he warns would-be teachers, "What you would teach, you must first know." That seems plain enough but it's easy to forget.

My personal hero, the profoundly literate British physicist John Tyndall, writes "... as a land of gas and furnaces, of steam and electricity ... I ask you whether [we have] not a right to expect from [our] institutions a culture [embracing] something more than declension and conjugation."

And Tyndall's mentor Michael Faraday, writing on the education of one's judgment says, "The world little knows how many ... thoughts [passing] through the mind of a scientific investigator have been crushed in silence ... by his own severe criticism."

They all see science as a mental rigor that'll make sense of their new technological world. But more is going on here. Youmans has tapped into the dynamic of the interaction of the old world with the new. While America looks toward Europe for knowledge, these Europeans respond to the energy and dynamism of our people.

We feel a subtle undercurrent. Europe's advice is actually feeding upon its American audience, and it's really directed at her own graying institutions. So much of the book's good advice was already exemplified in America. Our self-taught intellect had embraced wood, steel, and steam; and was now closing upon its established cousins with locomotive energy and speed.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

The Culture Demanded by Modern Life. (ed. E. L. Youmans) (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1897) This edition is an unedited reprint of the original 1867 book.

For more on Edward Livingston Youmans and William Jay Youmans see articles in the National Cyclopaedia of American Biography.