The Zephyr

Today, a silver streak. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

The year 1934 was when modern commercial airliners finally took form with their retractable landing gears, aluminum skins, and improved engines. Several companies build such planes and one, the DC-2, was the forerunner of the DC-3, which forever changed air travel.

By then, our huge country had been connected, coast-to-coast by rail for 65 years and crossing the country was generally a trip that took several days. Nineteen years later, I spent four hard days and three nights on a train from Seattle to Richmond.

Four years earlier, our 24-million new automobiles were already bringing the railroads under threat while airplanes were still an ignorable part of travel. The DC-3 was not yet on any horizon; so four companies, including GM and the Burlington & Quincy Railroad, joined to build a train for the future. They called it the Zephyr. When it was unveiled in 1934, it was to rail what DC-3s would be to flight.

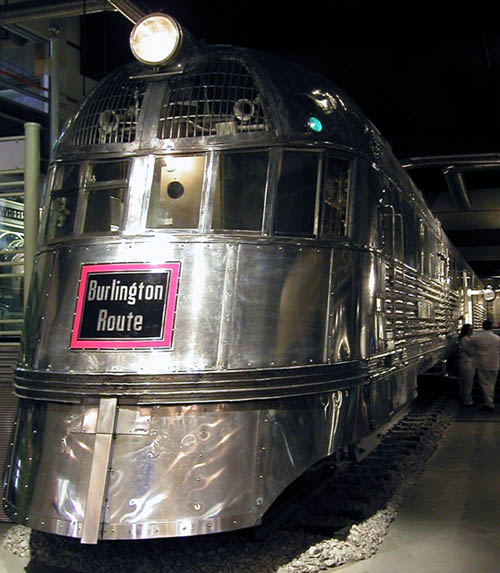

It was made of gleaming stainless steel and author Margaret Coel rightly likens it to Buck Rogers' rocket. Modern design was just moving from Art Deco to Streamlining, and the Zephyr helped lead the charge. Boss Kettering of GM oversaw the development of a radical "two-cycle" (that is literally a two stroke) Diesel engine to replace bulky steam engines.

It was made of gleaming stainless steel and author Margaret Coel rightly likens it to Buck Rogers' rocket. Modern design was just moving from Art Deco to Streamlining, and the Zephyr helped lead the charge. Boss Kettering of GM oversaw the development of a radical "two-cycle" (that is literally a two stroke) Diesel engine to replace bulky steam engines.

The train was a beautiful thing by any measure, and its unveiling lived up to its appearance. It left the factory on April 7th and headed for its maiden trip on May -- 26th a never-before-attempted, nonstop, dawn-to-dusk run from Denver to Chicago.

As the day approached, requests poured in for tickets. The 86 passengers on the short train included a burro named Zeph to represent Colorado transportation from another age. Movie stars and poli-ticians had to be turned away, but fifty thousand visitors got to tour the train during a brief two days before the run.

Then the trip itself; The Zephyr set records that've never been beaten. It made the 1015-mile run in 14-1/4 hours and it averaged almost 78 miles an hour. Margaret Coel reports that Diesel fuel for the entire trip cost less than seventeen dollars. Of course, that was during the Depression, and Diesel fuel cost only around four cents a gallon.

Eight more such trains were built upon the Zephyr archetype. And the original Zephyr ran for 25 years before it finally retired in 1959. By then it'd traveled more than 3,200,000 miles between Kansas City and Chicago, and the first jet airplanes were transforming American travel. They were moving us off the rails and into the sky.

The Zephyr's fate was being sealed even as it made that first incredible run to Chicago; but you can still see it today. There in the Chicago Museum of Science and Industry the Zephyr sits -- huge, gleaming, and as likely to take one's breath away as it was in Denver, some four-score years before.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

M. Coel, A Silver Streak. American Inventions: A Chronicle of Achievements that Changed the World (New York: Barnes & Noble, 1995) pp. 110-117.

As a matter of interest, the 1976 Gene Wilder/Richard Pryor movie Silver Streak was set on a later train, but the title paid homage to the Zephyr'snickname as well as to the 1934 movie The Silver Streak, which was about the Zephyr itself.

I took the photos below at the Chicago Museum of Science and Industry. The image in the text above is taken from one of my cherished coffee cups.

The Zephyr.

The luxurious rear observation car of the Zephyr

Cross-sectional profiles of the Zephyr: Front half above, rear below.