Science Remaking the World

Today, science and change. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

In the summer of 1922, Columbia University gathered in noted technical people to teach a course on science in everyday life. Our world was being transformed in a tinderbox reaction between radically new sciences and furiously inventive technology. They use the word science as an umbrella term for both science and technology as we understand them.

Sixteen of the lectures have been published in a book titled Science Remaking the World. They deal with coal tar, epidemiology, gasoline ... The stress always falls on the fancy word science, and some articles do deal with electrons or evolution. But the concern is with a world being rebuilt by technology.

The authors are intensely aware of change. They try to understand the perfect storm swirling about them, just as you and I try to understand the where today's information explosion is taking us.

Example, a chapter on tuberculosis lists the top six killer diseases. Tuberculosis had been number one, in 1900. But it's now dropped to third place, while heart disease has risen from third to first. Cancer first appeared on the list in 1920 and kidney diseases are also gaining on us. As water quality improves, number three killer, diarrhea and enteritis, drops off the list.

Example, a chapter on tuberculosis lists the top six killer diseases. Tuberculosis had been number one, in 1900. But it's now dropped to third place, while heart disease has risen from third to first. Cancer first appeared on the list in 1920 and kidney diseases are also gaining on us. As water quality improves, number three killer, diarrhea and enteritis, drops off the list.

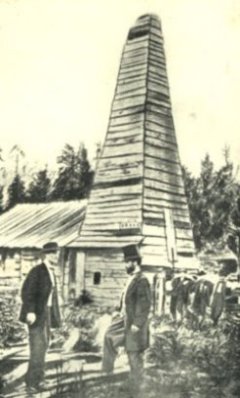

Two articles echo loudly today. The writer on gasoline (which he still spells as gasolene) observes that there's not enough petroleum to go around. He suggests two possible alternatives when it runs out -- shale oil and alcohol. (Remember, this was almost a century ago.) He also remarks that "No schools could teach mechanics as widely and practically as the auto has." That was still true when I was young; but we now no longer look inside our cars the way we once did.

We also might take a page today from the article on evolution. In one section, the writer talks about practical applications in agriculture. He shows how we use evolutionary breeding of plants in adapting them to disease and environment. In another, he talks about the way evolution can promote the development of a scientific spirit. He quotes this fine remark by Emerson:

God offers to every mind its choice between truth and repose. ... He in whom the love of repose predominates will accept the first creed, the first philosophy, the first political party he meets. ... He in whom the love of truth dominates ... will abstain from dogmatism.

And so the issues that haunt us today have been alive for a long time. They've shifted and modulated, but they're still there. What we read is no simple boosterism. The authors were as painfully aware of the dangers and difficulties that followed technology then, as we must be now. The editors conclude that "Exact knowledge and faithful interpretations of science," bring with them "large obligations." -- that "Modern science is dangerous."

And so it remains today. That threatening but wonderful genie is still loose. He hovers about us now, just as he did in 1922.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

Science Remaking the World. (Otis W. Caldwell and Edwin E. Slosson, eds.) (Garden City, NY: Garden City Pub. Co., Inc., 1922/1923). I am grateful to Sims McCutchan and Margaret Culbertson for giving me this very revealing old book.

For more on the temper of this period, see: J. H. Lienhard, Inventing Modern: Growing up with X-Rays, Skyscrapers, and Tailfins. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003).

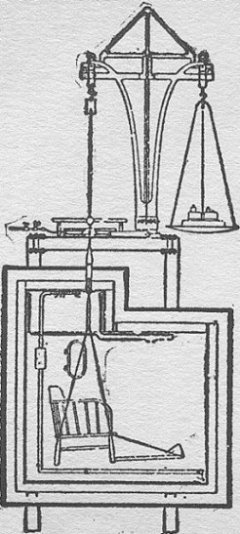

Images from the book: Left, a hanging chair calorimeter; Right, the first oil well.