Ghosts Teaching History

Today, we learn history from ghosts. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Driving from Kentucky to Oregon, many years ago, I'd just left South Dakota, and was grinding my way west, watching the sun sinking before me. I was low on fuel and looking for gas, when I came upon the Custer Battlefield -- an opportunity not to be missed.

I stopped, only to find it'd just closed. I could still get in, but everything was shut down. Not only was I low on gas, I didn't know if the gate would be locked when I tried to leave.

The first thing I saw was the hillside where the Northern Plains Indians surrounded and killed Custer and his men. A large central graveyard marked the site. Scattered crosses showed where men had tried to run and been cut down. There were also memorials to the great Indian victory over the invader.

Then another sign: Four miles onward, was the hilltop revetment where Major Marcus Reno had dug in and survived a two-day siege. So, all alone, with the sun setting, I shrugged off the frisson of fear, and motored on until I came to Major Reno's carefully cut trenches. I saw the sheltered gully where Reno's men had picked their way down to the river for water. One section was a field hospital.

I saw how he'd escaped to this protective knoll without knowing what'd happened to Custer. I gazed down at the Little Big Horn River, where thousands of Indians had camped. I could hear their shouts and movements in the dead silence. I had the same lines of sight that Reno had, and I knew the confusion of battle.

As light faded, a century dissolved, and I heard ghosts. No ectoplasm or voices, just a powerful presence of the past, heightened by the potential consequences of my own folly in being there.

So, think about ghosts. If we visit the original place, or we hold the artifact in our hand, and, if we find the right frame of mind, then something happens. Combine knowledge of the past with the physical object, and we can get much more than the sum of two parts. If the circumstances are right, we share something with those who once touched -- or who saw -- what we now touch or see.

We find history transcending dates and facts. We join the past by sensing its unique texture. We hear what it's telling us. The same thing happened to me when a Polish friend took me to see Auschwitz on a rainy weekday -- a day when we, and the ghosts, were the only beings in that desolate place.

But, put aside slaughter and genocide. Happier ghosts dwell in, say, old books. Look at marginalia in books from other centuries -- in books that've changed lives. As we read what readers have left in the margins, their ghosts reveal the transforming power of the written word in other ages. Or walk through old houses, for all houses are haunted in the sense that I offer the word.

And I leave you with this claim. It is, simply, that we never fully know any history until we quiet our minds, and listen to the people who once lived it.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

For an account of Custer's defeat, see: http://www.eyewitnesstohistory.com/custer.htm

For an account of Reno's and Benteen's survival see: http://www.eyewitnesstohistory.com/custercont.htm

Here is the website for the Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument: http://www.nps.gov/libi/

And here is an excellent map of the Battle of Little Bighorn.

On the sound track, two Native American songs are heard. The first, in the middle of the episode, is The Liggle Big Horn Battle Song, done by the Porcupine Singers, a Lacota Indian Group. The second, at the end, is the Fast Sioux War Dance, done by another group with appears on a CD titled, Authentic Native American Music.

The ideas in this episode are further developed in: J. H. Lienhard, How Invention Begins. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006 [in press]): Chapter 12.

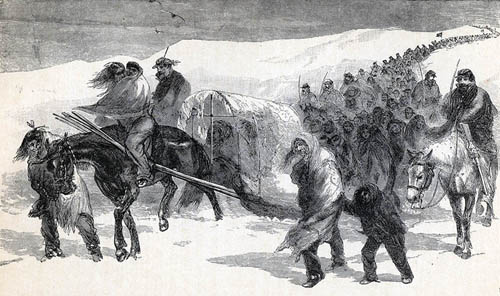

Example of the kind of litter used by Lt. G. C. Doane to move Reno's wounded to safety. Doane was one of the soldiers who came to his rescue. (19th-C US Signal Corp photo cited by O. H. & L. Bonney, Battle Drums and Geysers. (Chicago, Sage Books, 1970): pg. 60.

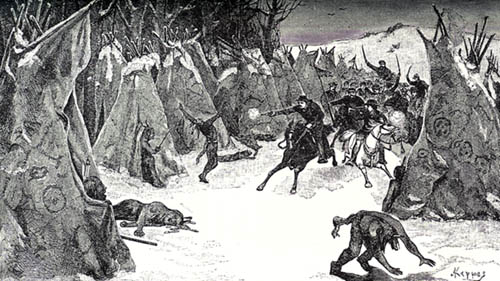

Above, the "Battle" of the Washita. Below, Prairie Indian Encampment

(Images from G. A. Custer, My Life on the Plains. (Reprinted from 1872/74 by Chicago, Lakeside Press, 1952))

Below, Indian prisoners (from E. B. Custer, Following the Guidon. (New York:" Harper, 1890): pg. 47.)