Mary Anne's Book

Today, a ghost in a book. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

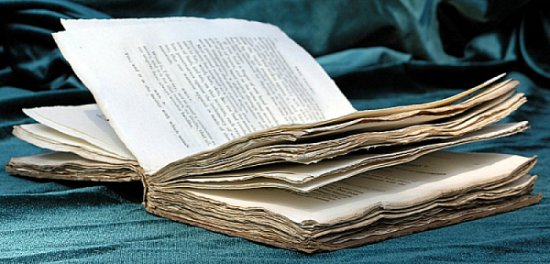

It just arrived in the mail -- an 1813 edition of Jane Marcet's chemistry text. Its format is duodecimo: That refers to large printed pages, folded into what're called signatures of, in this case, twelve leaves or twenty-four pages each. To make the book, the signatures were then sewn together. The folding was still done by hand, and the pages are rough and uneven. Book production was accelerating, prices falling, quantity winning out over quality. People who couldn't previously afford books, now could.

That's exactly why ghosts ride in them. You didn't carry a book, worth a month's pay, on a Sunday picnic. As books became more rough and ready, readers became more, not less, deeply invested in them. They begin writing in the margins. You find cracks in the binding and pages well-thumbed.

So what ghost can we summon from this two-volume set? Remember, ghosts are elusive; you never quite see them whole. A woman named Mary Anne Howley has signed mine. She turns out to've been the daughter of William Howley, who later became Archbishop of Canterbury. Howley was born around 1806, she married the eighth baronet of Beaumont, and died at the age of 28. Among her few traces is a letter from her husband telling the painter Constable that they won't be able to meet. Lady Beaumont has suffered "a violent relapse of the prevailing Epidemic." That was a year before her death, and five years after she gave birth to the ninth baronet.

Marcet's chemistry book came out when Mary Anne Howley was around seven. But her signatures now have the speed and fluency of someone older.

She probably read it as one of the teenagers for whom Marcet wrote it. Only the first two hundred pages of the first Volume have been cut. Someone has yet to take a letter opener to the remaining folded signatures. Howley appears to've been distracted about the time Marcet was explaining hydrogen.

But she got through the part on heat. And here's another teaser. Generations of Beaumonts were patrons of artists -- one of whom, Charles Leslie, did Archbishop Howley's portrait. And his father was an American instrument maker and friend of Ben Franklin.

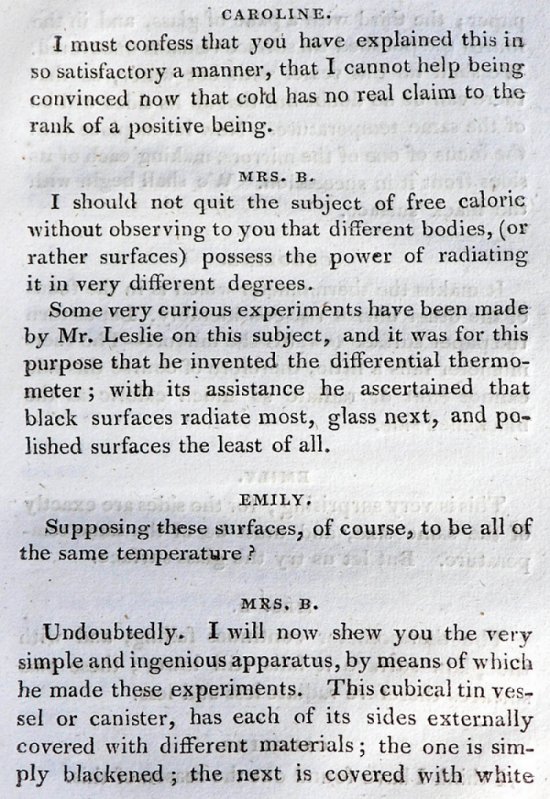

Marcet, who'd studied art, also did her own illustrations. She talks about an ingenious experiment on radiant heat (or free caloric, as she calls it) done by a Mr. Leslie. With Marcet's connection to the art world, I like to hope that might've been Charles Leslie's father, whose friend Ben Franklin had also experimented with radiant heat transfer.

And so ghosts, indistinct though they may be, whisper from the pages. Science and art were then undergoing huge changes, and determined women (like Marcet) were asserting a new role for women. If Mary Anne Howley failed to emerge from the shadows, just then, others would. Meanwhile, I hold these old books and know that others have held them before me. Perhaps as agents of transformation -- and, perhaps, only as talismans of hope for a better future.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

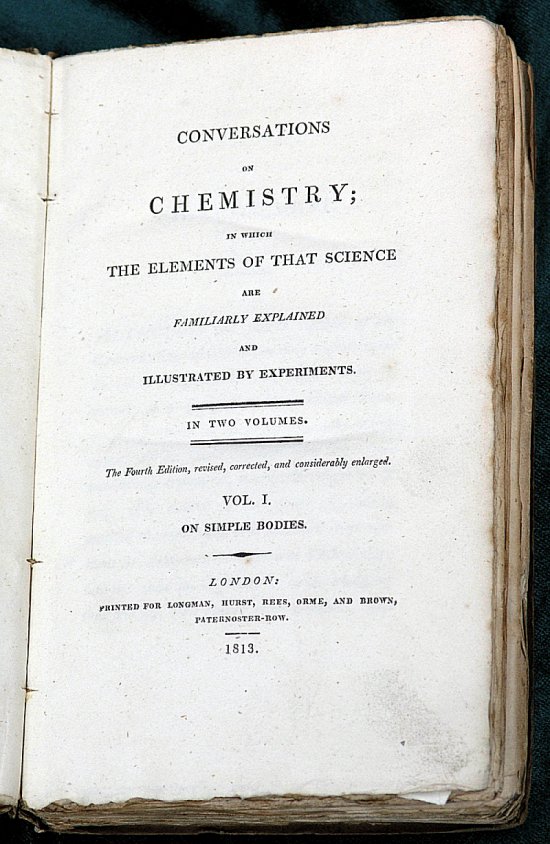

J. H. Marcet, Conversations on Chemistry; in which the Elements of that Science are Familiarly Explained and Illustrated by Experiments. In two Volumes. 4th ed. Vol. I. On Simple Bodies (London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown, 1813). (The source of the book was Maggs Bros. Ltd., 50 Berkeley Square, London W1J 5BA.)

Mary Anne Howley was an eldest daughter born after Bishop Howley's mar-riage in 1805. Since she was married in 1825, we can guess that her birth was in 1806 or 7. She died in 1834 of causes unknown.

For more on Jane Marcet, see M. B. Ogilvie, Women in Science: Antiquity through the Nineteenth Century. (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1986) pp. 125-127.

For more on the book, see M. S. Lindee, The American Career of Jane Marcet's Conversations on Chemistry. 1806-1853. Isis, Vol. 82, pp. 8-23.

One may find articles on William Howley, Sir George Howland Beaumont, and Charles Leslie in The Dictionary of National Biography.

I am grateful to Barbara Kemp, UH Library, for her great help in tracking down additional material on the Howley and Beaumont families.

Title page of Conversations on Chemistry

"I will now shew you the ... ingenious apparatus"