Greek War and Politics

Today, our guest, historian Robert Zaretsky, talks about the Greek use of war. The University of Houston presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Clausewitz famously wrote that war is nothing but the continuation of politics by other means. An example from ancient Greece reveals an unexpected depth to this dictum.

In Herodotus' History, a Persian commander, preparing to invade Greece, dismisses its inhabitants: they fight, he sneers, "out of mere ignorance and stupidity." Having arranged themselves on the "fairest and most level piece of ground" they simply charge one another. The result: great losses for the winners, even greater losses for the losers.

As it happens, at the battle of Marathon in 490 BCE, the Athenians behaved stupidly -- and won handily. How? Their tactics were inseparable from their politics. Historian Victor Davis Hanson invites us to reconsider the genius of the Greeks -- not only in the arts, but also in war.

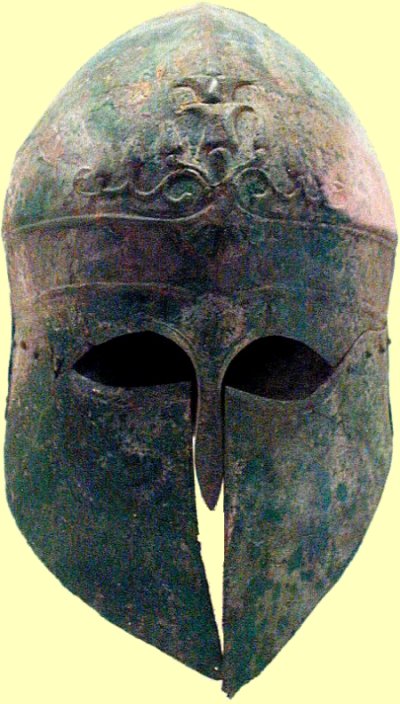

The Athenians who confronted the Persians were not trained soldiers. Rather, they were what the Greeks called hoplites: citizen soldiers who carried their own armor and weapons. The armor, which tipped the scale at sixty pounds, included a shield, called the hoplon. (How telling that these soldiers should be named after this particular tool!)

Usually ranged in eight rows, the hoplites formed a phalanx. Each hoplite's shield, held by the left arm, also protected the man directly to his right. Once having closed with the enemy, the phalanx's front rows bristled with spears and swords. And those in the back rows? They hunched behind their shields and they pushed. And pushed yet more, their goal to collapse the enemy line and thus end the contest.

The young fight our wars; in ancient Greece, war knew no age. Athenian hoplites were as young as 18, as old as 60, the old men (like Socrates) tempering the inexperience of young men. The poor usually fight our wars; in ancient Greece, war knew no class. Great merchants fought alongside modest landholders, artists next to artisans. The tragic playwright Aeschylus wished only to be remembered for having fought at Marathon. Hence the great morale of the citizen soldiers of Athens: not only was their democracy direct and participatory, so too was their view of war and death.

Citizens could not fight long battles: farms and vineyards would not wait. Thus the genius of Greek battle: it was nasty, brutish and short. A good thing too: once the battle was decided, the hoplites returned home, picking up again the private lives they had left behind.

Nietzsche wrote that the ancient Greeks were superficial out of profundity. With shock battle, it's as if the Greeks decided that sharper and shorter violence was more humane. It is only now that humankind has become truly stupid, maintaining ancient Greek tactics in an age of advanced technology, thus transforming armies into killing machines that the Greeks were incapable of imagining. Having taken this invention of the Greeks and made it grotesque, we can only envy their superficiality.

I'm Rob Zaretsky, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

Robert Zaretsky is professor of French history in the University of Houston Honors College, and the Department of Modern and Classical Languages.

V. D. Hanson, The Western Way of War: Infantry Battle in Classical Greece. (New York: Knopf, 1989)

Herodotus, The History. (translated by David Grene) (Chicago: Uni-versity of Chicago Press, 1987)

Greek helmet at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. (Photo by John Lienhard)