Etienne Jules Marey

Today, we try to build machines that work like animals.. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

French physiologist Etienne Jules Marey was born in 1830, and he trained in medicine and physiology. For the first ten years of his career, Marey focused on instrumentation. He measured the circulation and hydraulics of blood and breath, the elasticity, strength, and tone of muscle, the behavior of the heart. To do all this, he built a stunning variety of mechanical instruments.

At first it was pretty much measurement for measurement's sake. Then Marey began focusing on one particular question: How do animals move and birds fly? In 1873 he published the first of his many books: Animal Mechanism: A Treatise on Terrestrial and aerial Locomotion. His opening sentence is loaded. He writes:

Living beings have frequently been ... compared to machines, but it is only in the present day that the ... justice of this comparison [is] fully comprehensible.

Marey's hope has taken a beating since then. As we've tried to improve machines by copying animals, we've seldom succeeded. The design of animals is just too incredibly sophisticated. Still, Marey began a process that goes on today. Bit by bit, living creatures do reveal their secrets.

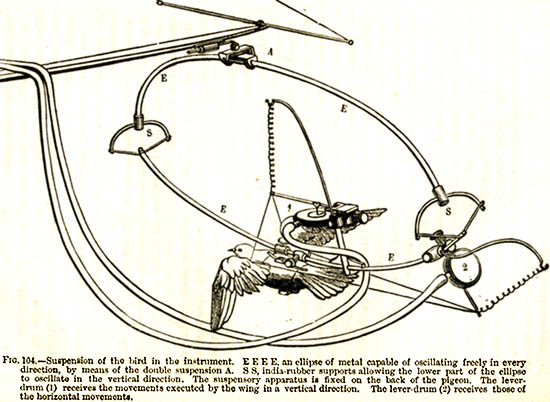

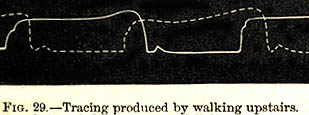

But Marey was looking in from the outside. He measured movements of limbs in humans and animals. His countless graphs showed the response to electrical shock, motion of feet and hooves, cyclic action of wings. He built a large rotating arm on which he mounted a live, instrumented bird that he could observe in flight.

My 1897 and 1911 Encyclopedia Britannicas (just before and after, the Wright Brothers) both have long articles on flight. Each quotes Marey's work. That's because, even after we began to fly, we still clung to the hope that birds would show us the best way to do it. Alas, they haven't yet. The means used by birds remain too subtle to copy.

Marey says, again and again, that it's just a matter of measurement. Measure the movements of birds accurately enough, and we should be able to replicate those motions. Then we'll fly. Yet, when he's done, we look at his glorious accretion of data and we still wonder just how we go about getting ourselves into the air.

Marey says, again and again, that it's just a matter of measurement. Measure the movements of birds accurately enough, and we should be able to replicate those motions. Then we'll fly. Yet, when he's done, we look at his glorious accretion of data and we still wonder just how we go about getting ourselves into the air.

Still, Marey made huge strides in the improvement of medical measurement. He died the year after the Wright Brothers flew, and he left us with a rich legacy of knowledge that we didn't have before.

But the Wright Brothers did not measure birds. They used a wind tunnel to measure the effectiveness of their own airfoils. In the end, what they showed us was a component of willfulness. Marey said, "I'll study the birds and copy them." The Wrights said, "Forget birds. We don't have millions of years. We must make our own beginning if we want to fly."

Invention is hubris. It is willfulness. The inventor knows that nature must only be obeyed, not copied. And it is a very rash thing to say, "Now I'll leave nature, and do something wholly new."

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

E. J. Marey, Animal Mechanism: A Treatise on Terrestrial and Aerial Locomotion. London: Henry S. King & Co., 1874. (Original French publication, 1873.)

In America we often hear of Marey on in connection with the photographer of animal and human motion, Eadweard James Muybridge. For more on that connection, see Episode 826.

Photo of birds in motion by John Lienhard. Other images from Marey.