Inventing the Street

Today, we invent the city street. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

As a child, growing into an awareness of the world around me, I was first conscious of my room and my parents, then of my house and the street in front. Next, I learned that I lived on a grid. My personal coordinate was 852 Holly Avenue. To the west, Holly intersected Victoria Street, to the east Avon.

So my measuring stick became the rectangular city block. In the short dimension, a block was two lots deep, with an alley splitting it down the middle. (The alley was where horse-drawn wagons, then trucks, made their deliveries.) In its long dimension, a block held ten or twelve houses on either side.

I grew older -- began walking, then biking, further and further from home. I learned about miles -- one mile was eight long blocks. And, to this day, and no matter where I am, I find ways to interpret my surroundings in terms of these old city blocks.

Of course, not everyone shares this coordinate-system view of the world. Nevertheless, a grid of city streets does pervade much of our thinking. That's why an essay by John Brinckerhoff Jackson got my attention. As Jackson studies cities, he finds that streets were a major stage in their evolution.

Early medieval towns were served by connecting roads, but once in town, those roads blurred. Look at old drawings of cities and what you see are only the masonry structures -- towers and spires. Wooden structures came and went. You see no streets. Instead, a rabbit-warren network of footpaths is buried within the city.

As cities grew, you began finding central market sections, served by roads that extended into the city. That change was driven, in turn, by the development of horse harnesses.

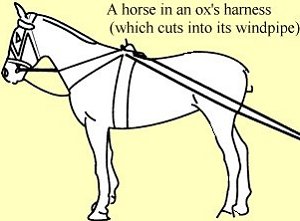

For Romans, oxen had been the major power supply for wagons and carts. It took a long time for people to realize that ox har-nessing strangled a horse's windpipe. We couldn't make full use of the horse in drayage until we'd first invented the horsecollar. But we still just carried goods into and out of a city square.

For Romans, oxen had been the major power supply for wagons and carts. It took a long time for people to realize that ox har-nessing strangled a horse's windpipe. We couldn't make full use of the horse in drayage until we'd first invented the horsecollar. But we still just carried goods into and out of a city square.

One more invention was needed before we could make use of a system of city streets within. That was a swiveled front axle that allowed wagons to negotiate tight turns.

By the thirteenth century, all that was in place. And cities were growing to sizes that could no longer be served by a single market area. Only then were systems of streets finally created.

And so, by the time westward-moving America built two new cities on the Mississippi -- St. Paul and Minneapolis -- their form would naturally be a clean rectangular grid of streets, almost from the start. That's why a rectangular coordinate system is so grooved into my Midwest consciousness -- horses in the alley, and cars on the street. (Even then, when we moved into that old house, it still had a concrete block on the front curb, to help visitors descend from their carriages.)

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

J. B. Jackson, The Discovery of the Street. The Necessity for Ruins and Other Topics, Amherst, MA: The Univ. of Mass. Press, 1980, pp. 55-66.

I am grateful to Drexel Turner, U. H. College of Architecture for providing the Jackson article.

Map of my childhood coordinate system. Image courtesy of Yahoo.com