Blombos Cave

Today, let's visit Blombos Cave. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

You and I have to struggle with our of Clan-of-the-Cave-Bearthinking: We've been trained to believe that, only about thirty-five-thousand years ago, the fine upright Cro-Magnons arose to displace the brutish Neanderthals. Well, that's all being turned on its ear by the Blombos Cave site.

Blombos Cave overlooks the Indian Ocean, on the south coast of South Africa. In 1993 it stunned the anthropological world when it yielded hundred-thousand-year-old, finely-formed, bone tools -- two or three times the age of such tools from Europe. And the people who made them were, anatomically, Modern Humans -- like you and me.

Let me give some benchmark dating here: the Paleolithic Era (which means the Era of Old Stone). It starts with the first human tool-making two and a half million years ago. It ends after the last Ice Age and the beginnings of agriculture. After that, we talk about the Neolithic Era (the Era of New Stone). It lasted until we took up metalworking, and we invented writing.

The older Paleolithic Era took place in two parts: Lower and Upper. During the latter part, the Upper Paleolithic Era, Modern Humans appeared and rapidly extended tool making beyond simple chipped rocks. For a long time, we'd believed all that'd started just a little over thirty thousand years ago.

But most of the evidence for that had come out of Europe. Now Blombos Cave has moved the rise of Modern Humans back to a time long before the Neanderthals vanished. It has tripled the length of the Upper Paleolithic Era, and it places the cradle of Modern Humans down at the far tip of the African continent.

Among those oldest-known bone tools we find spear points, awls, spatulas. We find standard forms of tools. We find the first evidence of fishing. We find fine stonework of a kind that didn't turn up in Europe until twenty-thousand years ago. We find different areas of the cave devoted to specific activities.

The most remarkable discovery is that of purely artistic technologies. Ochre was widely used. Ochre is a form of iron ore that makes a fine paint. It can be used on human bodies or on walls. And those chunks of ochre themselves have been scribed with abstract designs. The cave has also yielded up a seventy-five-thousand-year-old snail-shell necklace -- the oldest ever found.

All this suggests something beyond just tool making. These uses of an esthetic, symbolic language would hardly have been possible without speech, as well. And speech was also something we'd thought was only thirty thousand years old.

It's neat to find our grandparents doing so well, so long ago. As I was reading about that old necklace, my wife showed me a simi-lar one in a jewelry catalog. She said, "I guess we haven't come as far as we'd thought." Well, it's true. We really did not start being smart just the day before yesterday.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

J. N. Wilford, Tiny African Shells May Be Oldest Beads.New York Times, Science Times, Tuesday, April 20, 2004, pg. D3.

For more on the Blombos Cave site, see:

https://www.nsf.gov/od/lpa/news/02/pr0202.htm

I have not complicated this text by introducing the term Mesolithic. The Mesolithic Era was the relatively brief transition from the end of the ice age to the fully evolved agricultural Neolithic Era.

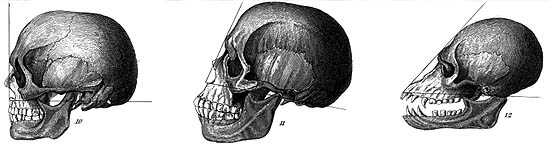

Nineteenth-century studies of skulls. From left to right: European, African, and ape. The theory was that the more vertical facial angle represented a more advanced race. Notice the African skull has been rotated clockwise to flatten the facial angle. Notice too, that the individuals have been selected to make the case. This kind of bias undoubtedly carried over, and slowed the realization that Africa is the probable cradle of modern hominids.