Cats in Ancient Cyprus

Today, a cat in Cyprus. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

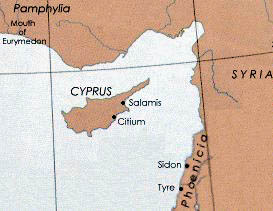

The island of Cyprus nestles into the northeast corner of the Mediterranean. Its long eastern peninsula points straight at the border between Syria and Turkey, only eighty miles away. The Island is rugged and mountainous. The date of the first human settlement on Cyprus is debated, but we're certain of a human presence starting about ten thousand years ago.

The island of Cyprus nestles into the northeast corner of the Mediterranean. Its long eastern peninsula points straight at the border between Syria and Turkey, only eighty miles away. The Island is rugged and mountainous. The date of the first human settlement on Cyprus is debated, but we're certain of a human presence starting about ten thousand years ago.

Those first settlers lasted two thousand years. They were pretty primitive at first, but they soon developed typical Neolithic skills. They made homes, art, and utensils, from stone. They wove cloth and they did some farming. They ate cereals and lentils. They hunted deer as well as pygmy elephant and pygmy hippopotamus.

They made no ceramics. They had no cattle. But they did have dogs. The people's lifespan was some 35 years and they stood about five feet tall. Infant mortality was high. It was a hard life.

Then, around eight thousand years ago, they vanished. We don't know why. But the island lay vacant for fifteen hundred years. Then a new population moved in with more advanced skills and a much better lifestyle.

Now a remarkable detail turns up among those first inhabitants. Anthropologists, excavating a very early settlement, have found a gravesite. The person (male or female, we do not know) had status. Polished stone tools and seashells -- emblems of wealth -- surround the body.

And, buried alongside the human is a cat. The reason that's remarkable is that we'd all thought the first pet cats were Egyptian -- much later than this. So then: was this a pet?

Its breed is felis silvestris -- the wild ancestor of the Egyptian cats. Its remains show no evidence of having been hunted down or butchered. This cat is entirely intact -- obviously a part of the wealth accompanying the honored dead.

So we wonder: Was this beast tame? By the way, the cats we know and love are largely tame; but many experts argue that they aren't really domesticated. They don't enter into human social life the way a horse or a dog might. Other questions begin nagging: Did this cat serve the community by reducing the rat population? Did it purr in its owner's lap?

Everything that puzzles us about this almost-ten-thousand-year-old cat -- this cat-in-the-wrong-place -- seems to've puzzled writer Joyce Carol Oates about her own cat. She writes:

The wildcat is the real cat, the soul of the domestic cat; unknowable to human beings, yet he exists inside our household pets, who have long ago seduced us with their seemingly civilized ways.

We can only guess at the soul of this cat. Those two curled up skeletons continue their separate, but parallel, play -- human and beast, together, yet apart. It's the same with our black cat: ignoring us, always in the same room, the same bed. She purrs, but her mind is in another place. Where? Maybe back in Cyprus.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

J.-D. Vigne, J. Guilaine, K. Debue, L. Haye, and P. Gerard, Early Taming of the Cat in Cyprus, Science, Vol. 304, 9 April, 2004, pg. 259. See also, The CNN article.

Ten thousand years later -- still thinking her own thoughts