Key West Railway

Today, we ride the Keys. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

The Florida Keys are a strange piece of America, stretching 128 miles from Homestead and Florida City out to Key West. I've never seen them. And I've always been torn between a wish to engage that remarkable road, and a fear that the drive might be slightly less interesting than watching paint dry.

The idea of a road from the mainland out to Key West arose before the automobile was any kind of major force in America. Writer T. A. Heppenheimer tells how it was first the brainchild of an aggressive developer, Henry Flagler, partner of John D. Rockefeller.

In the late nineteenth century, Flagler began building his way south through Florida. He built hotels, and a railroad line to serve them. When he reached the tiny village

of Palm Beach, he built a 540-room luxury hotel. Palm Beach was never the same.

He built a hotel on the Miami River and the city of Miami grew up around it. When he ran out of mainland, Key West beckoned him off into the Gulf. In 1905, 75-year-old Flagler asked if a rail-road could be built along the Keys. His general manager said it could, and Flagler replied, "Very well, then. Go to Key West."

The Florida penal system was then using prisoners as forced labor. The 1911 Encyclopaedia Britannica devotes a whole section to that system. These workers could be had for two-and-a-half dollars a month, but there weren't enough of them. When Flagler offered $1.25 a day to laborers from New York, bums turned up. Then, he found that local black laborers made a far superior work force.

And so the railroad headed out into the gulf. Many of the Keys were worthless coral or saline swamps. No fresh water -- it had to be brought in by boat. New means for pouring concrete below the surface of the sea had to be invented. The workers had to weather hurricanes and cover vast stretches of open water. The Seven-Mile Bridge section was the longest bridge ever built.

Finally, at a cost of twenty-seven million, turn-of-the-century dollars -- and two hundred lives -- the railway was finished. That old Britannica shows it complete, although work was still going on. In 1912, Flagler -- now 82 years old and blind -- rode his private railway car all the way to Key West.

Flagler was a formative agent in America's gaudy Gilded Age. And he helped to shape the Florida we know. Yet his railroad was not destined to survive the Great Depression. It was already in trouble in 1935. Then a terrible Hurricane struck it, killing three hundred people along the Keys, and stopping rail traffic. After the hurricane, the company abandoned that part of the line.

But state highway planners took it over. They used its superb system of viaducts and bridges to complete a highway to Key West, in 1938. Now that road over scattered islands and open water is studded with hotels and luxury along the way. I go to the web to bask in all that surviving elegance. I'll have to find a way to make that long drive one day, after all.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

T. A. Heppenheimer, The Railroad That Went to Sea. Invention & Technology, Vol. 19, No. 4, Spring 2004, pp. 54-62, and cover.

See also the article on Florida in the 1911 Encyclopaedia Britannica.

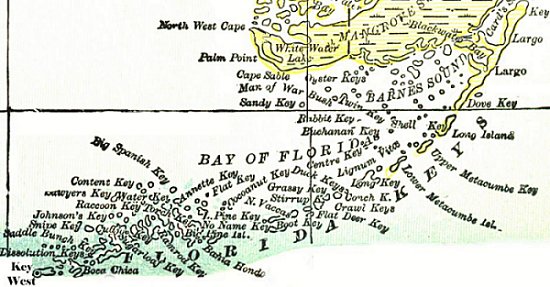

The Florida Keys (as shown in the 1897 Encyclopaedia Britannica)