The Fourth Man

Today, the Fourth Man. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

An article in the New York Times, about chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, calls my mind to the Kentucky blizzard of December, 1978. I'd been in a long committee meeting. Thick clouds of second-hand smoke had triggered a life-threatening asthma attack.

My wife managed to ferry me through snowdrifts to the Veterans Hospital. There I lay in a four-man room as doctors struggled to nudge my blood oxygen above the fatal borderline.

One of the four recovered while I was there. One was drugged out, probably dying of pulmonary disease and strapped to his bed. All night he'd shout at me, demanding I come over and untie him.

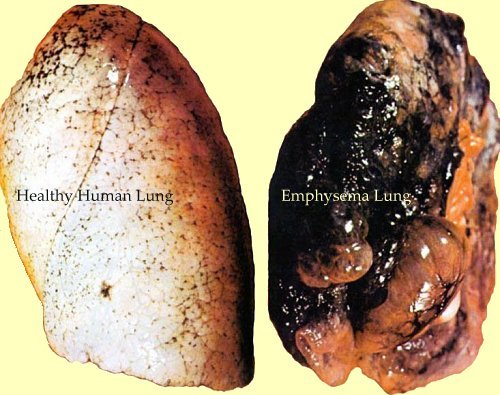

But it was the fourth man who haunts me, even now. He lay like King Tut upon his bier, barely breathing -- skin like translucent vellum over veins and bones. He emerged now and again from the haze of his suffocating emphysema for a few minutes of lucidity. And, during those moments, I extracted his story.

He'd been with the Army in the Philippines, captured at the beginning of WW-II. He'd made the ghastly march up Bataan Peninsula. Of 76,000 men who began it, 20,000 were killed -- beaten to death, bayoneted, and suffocated. Many were forced to dig their own graves, and were then buried alive. Here in this pulmonary ward, I was once more a twelve-year-old boy who'd been given night-mares by images of those living burials in Life magazine.

Now this survivor, likewise struggling to inhale air. He would soon die, and the odds that his was a smoking death are given by the Times article. Eighty-five percent of chronic breathing cases are caused directly by smoking and the rest by industrial pollutants and secondhand smoke.

Since 1965, the percentage of American smokers has been cut in half, with far more men than women quitting. But, with the population increase, the total number of smokers has hardly changed. The number of former smokers in America has tripled in that time.

Add to smokers, the vast number who've quit smoking, but whose lungs and bronchial passages have been damaged, and you get nearly a hundred million. The insidious thing about these diseases is that half the existing cases are undiagnosed. Thirty-five million Americans now live with chronic shortness of breath, many not real-izing where it's taking them. Perhaps I should mention billions in health care costs, but what's that against the cost in human life?

Tobacco remains as addictive as heroin and more deadly since it's a legal over-the-counter drug. And lung cancer is only one of its modes of attack. Pulmonary disease is an equal threat.

That old soldier, that fourth man, won his first war. Now you and I have to win the war against the disease that finally claimed him. And we can: Keep the prime enemy in sight. Give the tobacco industry no quarter. This time you and I are in the trenches -- we and those we love. This is our war, and we can win it.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

J. E. Brody, Just a Few Simple Steps Can Keep the Air Flowing Freely. New York Times, Tuesday, Feb. 10, 2004, pg. D8.

I am grateful to Stanley J. Reiser, University of Texas Medical School, for his counsel.

The National Institute of Health provides this excellent Medline site on smoking: http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/smoking.html

This image of healthy and unhealthy lungs was adapted from examples which appear in both web sources above.