Clark and Bronowski

Today, Kenneth Clark and Jacob Bronowski. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Clark and Bronowski defined the television historical documentary as we all know and expect it today. Their two series were named Civilisation and The Ascent of Man. And we have yet to surpass either one.

Art historian Clark used art and architecture as his window into the formation of civilization. Biologist Bronowski generally used science. But both saw far beyond any one field. Both knew perfectly well that, if you truly understand your subject -- whatever it might be -- it will, necessarily, embrace all subjects.

Bronowski, for example, takes us to the Alps in the summer of 1847. British physicist James Joule is at the foot of a waterfall trying to measure a temperature rise in water that's fallen from the cliff above. Bronowski goes on to mention that Wordsworth had visited this same spot 57 years earlier, and he had written,

For nature then ...

To me was all in all -- I cannot paint

What then I was. The sounding cataract

Haunted me like a passion.

Bronowski continues,

Joule never said it as well as that. But he did say, "The grand agents of nature are indestructible," and he meant the same [thing.]

Clark goes the other way. Listen as he starts with art and arrives at science,

People sometimes wonder why the Renaissance Italians, with their intelligent curiosity, didn't make more of a contribution to the history of thought. The reason is that the most profound thought of the time was not expressed in words, but in visual imagery.

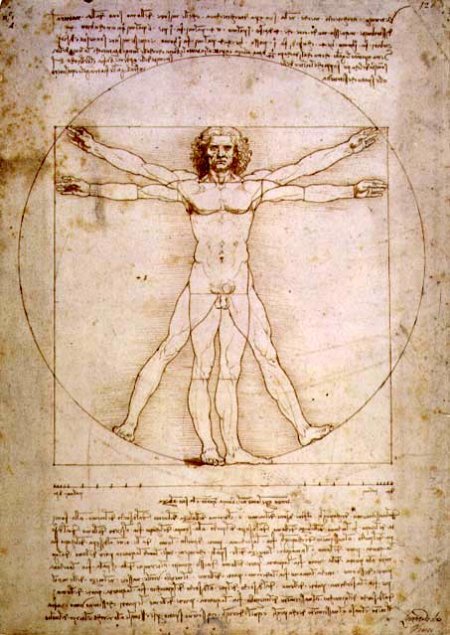

That remark immediately summons up Leonardo da Vinci. Both Clark and Bronowski have a lot to say about him. Clark says, "[We're] worn out by [his] energy. He won't take yes for an answer. He can't leave anything alone." Then you realize that art historian Clark is describing Leonardo as a scientist.

In Bronowski's piece The Long Childhood (about the evolution of the our brains) he offers Leonardo's Madonna of the Rocks as an expression of our struggle to grow. He sees Leonardo's anatomical sketch of a child in the womb as a universal expression of hope.

Watch either of these TV series by itself and I promise you'll be enchanted. But watch both, and you'll see a stunning convergence from two directions. Clark and Bronowski converge on hope, they converge on belief, they converge on the pervasive unity of the human species. Of course both are wary. In the end, Bronowski says,

We are all afraid ... That is the nature of the human imagination. Yet [we have] gone forward. ...

And a worried Kenneth Clark, facing the social upheaval of the late '60s, says (as much to himself as to us),

... civilisation has been a series of rebirths. Surely this should give us confidence in ourselves.

They both clearly assert our capacity for saving ourselves. They realize that technology, science, and the other arts have always converged upon our problems. And they surely remain our only real hope in troubled times.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

J. Bronowski, The Ascent of Man, Boston: Little, Brown and Company. 1973.

Sir K., Clark, Civilisation: A Personal View, New. York: Harper and Row, Publishers, 1969.

Leonardo's version of the Vitruvian Man