Anne Morrow Lindbergh, and Quiet

Today, a glider pilot seeks quiet. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

We best know Charles Lindbergh's wife, Anne Morrow Lindbergh, for her 1955 book, Gift From the Sea. It changed our view of the ocean, by making the sea into a metaphor for life itself. She tended to do that -- to encode parts of her life that did not yield to mere exposition, and thus make them understandable.

Of course we do that with our technologies, since machines are also metaphors for some deep-seated part of ourselves. Now I learn about a particular machine that Anne Morrow Lindbergh subsumed into her rich metaphorical subtext. It was the glider.

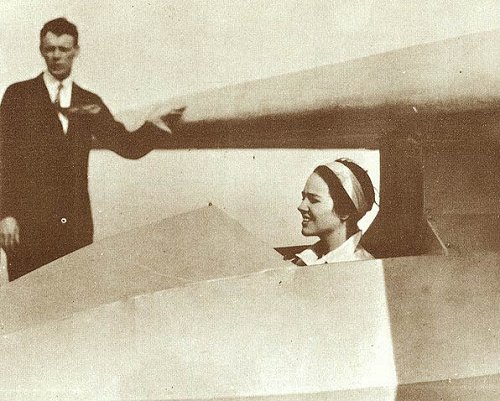

Anne Morrow and Charles Lindbergh married in 1929, a year after she graduated from Smith College. She already had a great deal of aerial experience by the time she learned to pilot a Burnner-Winkle Bird biplane, in 1931. She'd navigated for Charles; then she'd become the first American woman with a first-class glider pilot's license.

The newlywed Lindberghs had gone to San Diego to study with the noted glider-maker, Henry Hawley Bowlus. There, they both gained first class licenses. And they did so just when the press paparazzi were hounding them most unmercifully.

Anne Morrow Lindbergh speaks very directly to that experience in her book, The Unicorn and Other Poems. She writes,

Free as a gull,

Alone upon a single shaft of air

Invisible there,

Where,

No man can touch,

No shout can reach, ...

Anyone, riding updrafts in an engineless craft, finds that reverence for quiet. Anne's daughter Reeve said to me, "I don't know if she ever wrote it down, but mother told me that 'the cure for loneliness is solitude'." Anne had also told Reeve about "columns of air, stretching like massive tree trunks between earth and sky."

Although Anne Lindbergh did glider flying only during that brief period, the experience nevertheless held a central place in the rest of her life. That strongly emerges from another book, Hour of Gold, Hour of Lead -- a collection of Anne's correspondence beginning just before her marriage to Charles, and continuing through the kidnapping and death of their first child.

The glider experience is an important part of her three-year hour of gold. Her first solo flight was, she said, "perfectly serene and happy." In the misery of her subsequent hour of lead, the metaphor continues to serve her. Now she writes,

In that airy quietness ...

I would think until I found ...

Something lying on the ground,

In the bottom of my mind.

That echoes from my own childhood. I would dream of gliding above the clamor -- soaring in the whispering quiet, of which she writes,

A word falls in the silence like a star,

Searing the empty heavens with the scar

Of beautiful and solitary flight.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

A. M. Lindbergh, The Unicorn and Other Poems. New York: Pantheon Books Inc., 1956. (The first and last poems from which I quote are from this source. They are titled, Even and Space.)

A. M. Lindbergh, Hour of Gold, Hour of Lead: Diaries and Letters of Anne Morrow Lindbergh 1929-1932. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1973.

For more on A.M.L. as a pilot, see, http://www.charleslindbergh.com/anne/index.asp

I am very grateful to: Bob Phillips, UH Creative Writing program for substantial counsel; Reeve Lindbergh Tripp (daughter of Charles and Anne Morrow Lindbergh) for the fine insights she provided; and writer and glider pilot Alexis Glynn Latner for both pressing me to do the episode and for additional information.

The Lindberghs: Anne in the cockpit of a Bowlus glider and Charles standing. Jan. 31, 1930.