Celebrating "Progress"

Today, do I dare to celebrate progress? The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Historians dislike the word progress. It grows murky when we ask what we're progressing toward — what outcomes we're willing to accept as progress. Constant change surely is a mark of the human lot, but to identify change as progress, we need to see some resulting improvement of the human condition.

As an extreme example, ask if the development of the atomic bomb was progress. In the short term it may or may not've been responsible for ending WW-II. In the long run, we wish it didn't exist because it does far more collateral damage than sane people are willing to inflict.

But negative consequences follow all technologies and yet their net effect is that we live longer and fuller lives. An article in an 1889 Scribner's Magazine set me to thinking about all this. It's about railway mail service and it is a pure paean to progress. The new railroads had been delivering mail for fifty years, but by the end of the Civil War the system was still casual and haphazard.

The article tells how one George S. Bangs created rapid, and efficient rolling post offices during the early 1870s. And it explains how they work. The U.S. Post Office had finally placed its own mail cars on commercial trains. Commercial railways were, by the late nineteenth century, the primary mode of cross-country travel, and they'd become very reliable. Those postal cars combined their own enormous efficiency with that of the railways.

The article tells how one George S. Bangs created rapid, and efficient rolling post offices during the early 1870s. And it explains how they work. The U.S. Post Office had finally placed its own mail cars on commercial trains. Commercial railways were, by the late nineteenth century, the primary mode of cross-country travel, and they'd become very reliable. Those postal cars combined their own enormous efficiency with that of the railways.

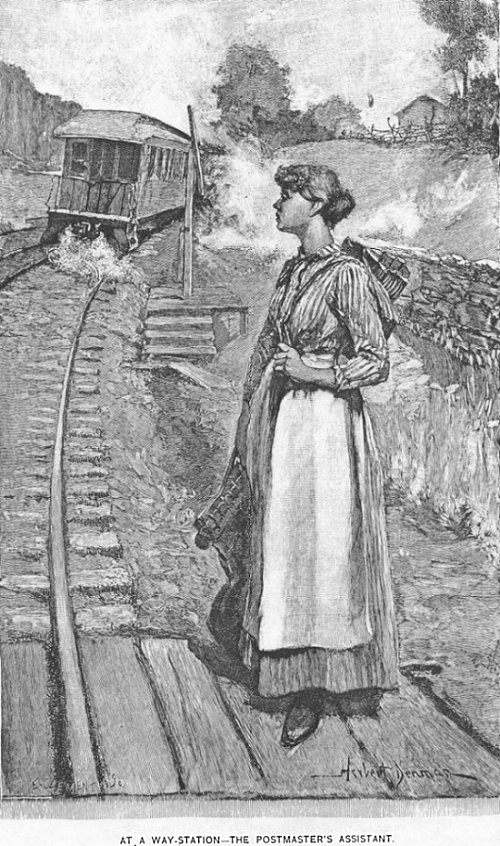

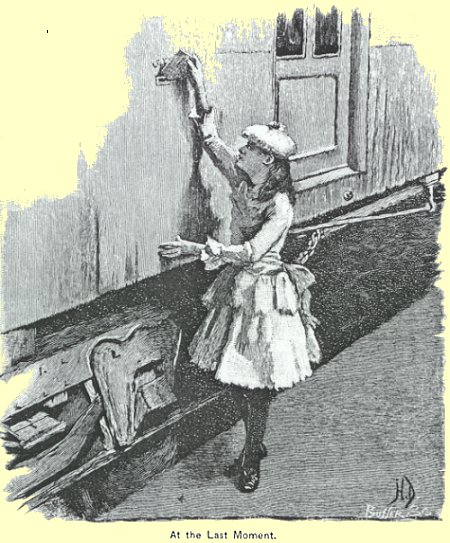

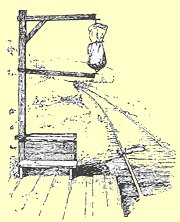

Postmen in the cars received bags of mail earmarked for the states along their routes. During the trip they sorted and subdivided the mail. They were equipped with devices for snagging new sacks of mail as they whistled past towns without stopping, and for dropping sacks off. The success of the system depended, in no small part, on creative incentives for attracting and keeping really good people who could work with focus and concentration.

Fifty years later I was a young boy. For three cents I could get my box tops across the country in two or three days, and receive my Captain Midnight decoder ring in a week. By then, you could pay much more for airmail, but it wasn't a whole lot quicker. Not until we had email would we make significant improvement over those old postal railroad cars.

So this really did look like progress. Now email is demanding a massive new social adjustment. We'll struggle before we learn to use it with equanimity and grace. But our grandchildren will surely overlook all the problems, and look back upon email as marvelous progress in its time.

I'll keep dodging talk of progress. I'll wear my doubts like a shield against excess. But do I believe in progress? Well, I wouldn't think of it. Never mind that I've far outlived my life expectancy at birth, that I really do like my TV and air conditioning, and that being with you all on a modern radio is a great joy.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

T. L. James, The Railway Mail Service. Scribner's Magazine, Vol. V, No. 3, March 1889, pp. 258-277. I am grateful to Pat Bozeman, UH Library, for providing a copy of this article and suggesting an episode based upon it.