Raymonde de Laroche

Today, the first woman pilot. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Finding the first of anything is always a dicey business, but the first woman to pilot an airplane seems to've been Raymonde de Laroche. We pick up her story in 1908: The Wright Brothers had set up camp at a race track near Le Mans, in France. They made 120 demonstration flights over their few weeks there.

The 22-year-old de Laroche had known of Santos-Dumont's first airplane flight in France, two years before. But now she not only got to see an airplane in the sky; she was even given a ride in it.

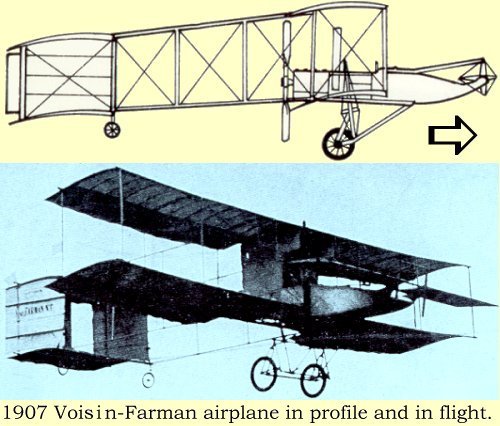

Aerial historian Eileen Lebow tells how de Laroche went to pioneer airplane-builder Charles Voisin, wanting to learn to fly. Voisin was quite smitten with the lovely Raymonde and he gave her special attention. They became close friends. And, on October 22, 1909, she became the first woman to pilot an airplane.

Aerial historian Eileen Lebow tells how de Laroche went to pioneer airplane-builder Charles Voisin, wanting to learn to fly. Voisin was quite smitten with the lovely Raymonde and he gave her special attention. They became close friends. And, on October 22, 1909, she became the first woman to pilot an airplane.

These new machines were terrifyingly dangerous. De Laroche suffered a crash ten weeks after she'd first flown. It was caused when the tail of her airplane brushed a tree during a landing. She suffered a concussion and a broken collarbone.

But she mended, and she did not lose her passion for flight. She was soon off to an air show in Egypt with Voisin's group. Then, on her return, she became the first woman anywhere to receive a pilot's license. Next she was off to fly before Czar Nicholas in St. Petersburg. There, Russians began referring to her as la Barrone de Laroche. She was not an aristocrat, but the title stuck. It fit her regal bearing, and it served her well at exhibitions.

An air show in Budapest, then one back in France where she flew into the wake of another airplane. She was knocked into a dive and crashed, breaking several bones. She returned to flying. Then a third near-fatal accident occurred a year later — this time on the ground. She and Voisin had a terrible automobile accident.

That crash killed Voisin, and she again was seriously injured. She recovered once more, and she kept on flying until WW-I began. Then all women flyers were grounded. During the war she worked as a driver for the French army, chauffeuring officers through artillery fire.

1919 found Raymonde de Laroche back in the air, in far more advanced airplanes. She set two women's altitude records — one at sixteen thousand feet. Then a test pilot offered her a ride in a new experimental plane. It slipped into a tailspin and crashed. She died outright, and the pilot died on the way to the hospital.

Flying was such a lethal business. Raymonde de Laroche had miraculously survived three serious crashes before the fourth one claimed her. The most amazing thing about her amazing story is that she was still alive, ten years after she first flew.

Few complex technologies have ever developed as rapidly as flight did. What a terrible toll in human life it took to bring air travel to the point where it's about as exciting as going to the grocery store.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

E. F. Lebow, Before Amelia. Washington, D.C.: Brassey's Inc., 2002, Chapters 1 and 2.

For more on early women fliers, see: J. H. Lienhard, Inventing Modern: Growing up with X-Rays, Skyscrapers, and Tailfins. New York: Oxford University Press, August, 2003, Chapter 10.