The Milk of Human Kindness

Today, the milk of human kindness. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Psychologist Robert Levine goes looking for the Good Samaritan -- for the kindness of strangers. How do strangers respond if we're in trouble? Levine wisely recognizes that the impulse to give aid is best revealed, not in the heroic act, but in the minor one. How alert are we to the small needs of those around us?

So he and his students set off for cities around the world with a set of five simple tests. The first three work pretty well: He pretends to drop a pen accidentally. How many strangers retrieve it for him? He stands at an intersection with dark glasses and a white cane. How many strangers offer to help him across the street? Walking with a leg brace, he drops a stack of magazines. How many strangers help him pick them up?

Two more tests were failures for cultural reasons. Drop a stamped letter; how many strangers pick it up and mail it? In El Salvador, there's a well-known scam in which an accusing bully appears to claim that he'd had money in an envelope he'd dropped. In Tel Aviv, it could be a letter bomb. In countries with high illiteracy, too many people just don't connect with it.

Another failed test involved asking people to change a coin. In poor countries, poverty made that impractical. In wealthy ones, it was implausible. In the end, the least culturally-biased tests were the ones with a pen, a cast on the leg, and a white cane.

Levine ranks cities around the world. Rio de Janeiro and San Jose, Costa Rica did best. Indeed, all the Spanish-speaking cities did well. New York and Kuala Lumpur were in last place.

But Levine casts a dimension of skepticism on his own study as soon as he starts explaining the different behaviors. New Yorkers filled their need to give assistance at the same time they avoided the dangers of contact. Without breaking stride, a pedestrian shouts, "Hey buddy, you dropped your pen." Or she might say to the blind man, as she walks by him, "The light's green. You can cross now."

Spanish and Portuguese, however, have a word we all know, but which does not translate well into English. The word simpático reflects a deep belief that any good person has the quality of being agreeable, pleasant, good-natured, and supportive. If you fail to pick up the pen and return it, you are not simpático.

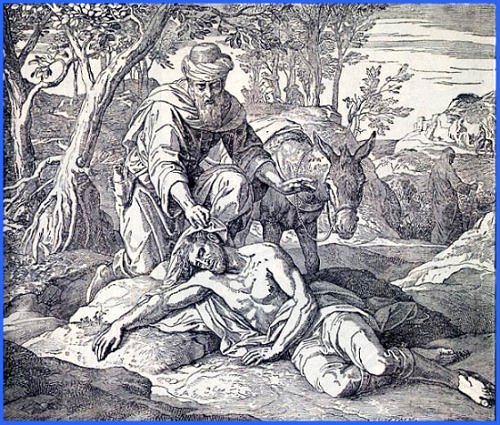

I suppose Levine's study does less to discriminate among cities, than to diagnose how we express our humanity in varying situations. No one people is better or worse than any other. I have to remind myself that the Good Samaritan was an outcast. He was someone the traveler would normally have ignored on the street.

Yet that does not stop me from crowing just a bit. You see, my own much-loved city of Houston, Texas, ranks second in the United States. And that's something I'm aware of, living here in Houston. We're very close on the heels of the leader, which happens to be Rochester, New York, and we are far ahead of Dallas.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

R. V. Levine, The Kindness of Strangers. American Scientist, Vol. 91, May-June, 2003, pp. 226-233.

Image of the Good Samaritan and the traveler, from a nineteenth-century German Bible