Farbenlehre

Today, light and color. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

When you think of the towering German writer Goethe, what comes to mind? Literature and philosophy, Faust, and the beginning of German Romanticism. But Goethe was proudest of his Farbenlehre -- his scientific treatise on colors, published in 1810.

The Farbenlehre reflected a new anti-Newtonian mood that was driving many scientists. In the minds of many, rationalism had run its course and was bankrupt. Goethe especially disliked Newton's work on the light spectrum. Newton had worked in a clean environment, free of the stray variables that so influence color.

So Goethe made his own vast study of light and color. But after he'd made his experiments and talked about their implications, he went on to dissect Newton himself. Newton had died nearly a century before, but he still ruled physics. And, while many of Goethe's criticisms may've been valid, Newton's optics was on pretty solid footing. So physicists brushed the Farbenlehre aside, despite the wealth of observation within it.

Years later, in 1878, Thomas Carlyle called upon the great British physicist John Tyndall. Tyndall had been deeply influenced by the Romantic poets and writers like Carlyle who'd followed them. They'd been saying that science had to arise within the human heart and head, as well as out of detached observation.

Science had listened, and it'd made a great leap forward. Now Carlyle gave Tyndall his old multi-volume set of the Farbenlehre. Tyndall read it with unfolding awe. Never mind theories of light; Goethe's experiments had shown how the mind mixed light to produce color -- how the mind forged illusion in doing so.

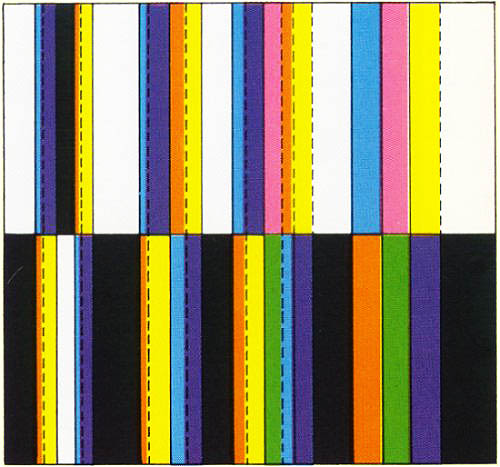

Two essential ideas ran through the work. The first was that color is meaningless to the mind without the boundaries that inevitably frame any image. The other omnipresent factor is turbidity -- cloudiness or particulates in the medium between the eye and the object. Goethe showed how our perception of color changes with boundaries or with turbidity.

Those ideas rang true with Tyndall. In an important experiment, he'd created optically pure air and shown that organic matter cannot putrefy in it, because it doesn't support bacteria.

As Tyndall reads the Farbenlehre he recalls Goethe's short poem, Wanderers Nachtlied:

Over all the hilltops

Is peace.

In all the treetops

You sense

Scarcely a breath of air;

Birds are hushed in the woods

Only wait -- soon

You too shall find rest.

Tyndall had done his share of hiking in the mountains. He talks about the altered color that this stillness of the air, this reduction of turbidity, presents to the wayfarer. It is a strange fusion of poetry and physics. Tyndall finishes with a last sad look at Newton and Goethe, and he laments the way poets and scientists exclude one another. Each, after all, brings unique tools to the essential task of helping us to see the true color of things.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

J. Tyndall, Goethe's Farbenlehre. New Fragments, New York: D. Appleton and Co, 1897, pp. 47-77.

J. W. von Goethe, Theory of Colours. (tr. Charles Lock Eastlake) Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1970.

As a matter of interest, Goethe is regarded as a Romantic by most English-language scholars. Many German scholars, however, regard him as being a classicist, separate from German Romantic writers like Heinrich Heine. In any case, his later writings strongly advance the thinking of the Romantic writers and poets.

The German text of Goethe's "Wanderers Nachtlied" is as follows (and I take responsibility for the free English translation above):

Über allen Gipfeln

Ist Ruh.

In allen Wipfeln

Spürest du

Kaum einen Hauch;

Die Vöglein schweigen im Walde!

Warte nur, balde

Ruhest du auch.

My thanks to James Pipkin, UH English Department, and Jack Hall, UH Library, for their counsel on this episode.

Goethe demonstrates the influence of boundaries on our perception of color in his Farbenlehre.