Radio Days

Today, listen, with me, to an old radio. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

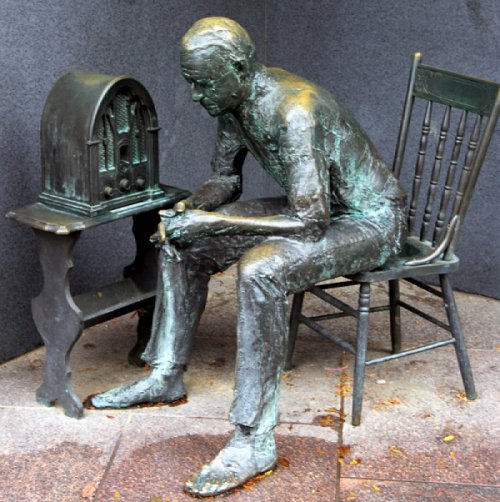

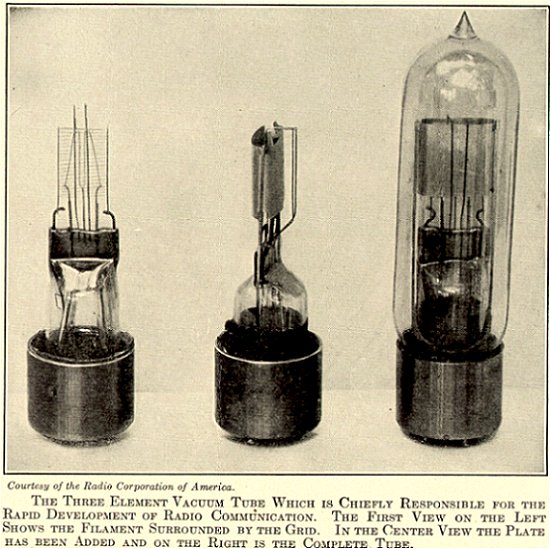

Childhood in the late 1930s: The vivid image of my family gathered around the radio in the evening. It was a modest wooden box with a rounded top. But, look in its open back, and you'd see its bright glowing tubes -- an amber Christmas crèche, that had the mysterious power to pluck adventure out of the aether and bring it into our living room.

Childhood in the late 1930s: The vivid image of my family gathered around the radio in the evening. It was a modest wooden box with a rounded top. But, look in its open back, and you'd see its bright glowing tubes -- an amber Christmas crèche, that had the mysterious power to pluck adventure out of the aether and bring it into our living room.

After school we'd listen to The Lone Ranger and Jack Armstrong. But in the evening it was the grownup stuff: Jack Benny, Fred Allen, all kinds of good music. Naturally, I'll never forget that October evening when my father tuned in to the Mercury Theater, just a minute or two late. An agitated network announcer was telling about a huge meteor that had landed in central New Jersey.

Then he switched to a mobile unit. Something strange was happening. Something was coming out of the crater -- something alive!

And the game was afoot. This was the most famous single radio show ever broadcast -- Orson Welles's version of H.G. Wells's story, The War of the Worlds. By 7:15 the full fury of the invaders from Mars was clear.

They were moving across America, toward my gentle home in Minnesota, killing everyone and everything in sight. When the station break came, I laid my delicious thrill of terror before my father. Was this real? I asked. He smiled and said, "I don't know. We'd better stay tuned." I was almost disappointed when it turned out to be make-believe. Earth was safe -- at least until World War II.

Radio served the same function that Grimm's fairy tales had served for children of an earlier time. It stretched our minds. It showed us the world of good and evil, honor and deceit, pain and pleasure. It sketched the story and let our imaginations fill in the details.

I listened as Joe Louis -- larger than life -- destroyed the German champion Max Schmelling in the first two minutes of the first round. (None of us suspected, after that beating, that Schmelling and Lewis were actually friends, and that their friendship would remain intact after the war.)

I was there listening when the announcer at the landing of the Zeppelin Hindenburg in Lakehurst, New Jersey, saw it catch fire. His voice rose over the crackle of static and flames while he watched what no human being should ever have to watch. I learned the difference between fantasy and reality when he broke down and wept, Oh, the humanity!

All that seems to've happened only yesterday. And, at the same time, it seems a thousand years ago. Most commercial radio today seems bent on fragmenting our attention -- whatever falls between commercials has to be simple enough not to distract us from the commercial.

The radio of my childhood was more naive. It copied the stage -- the theater -- the town meeting. It engaged us; it led us into our right brain; it touched our hearts; it made us free. It did what Public Radio still strives to do today.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

This is a greatly revised version of old Episode 195.

Sculpture of 1930s radio-listening found at the FDR Memorial in Washington, DC. It is remarkably faithful to radio-listening as I recall it from childhood.

(Photo by John Lienhard)

An advanced radio tube in 1923 (Wonder Book of Knowledge, 1923)