Reckless and Careful

Today, some thoughts about recklessness and caution. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

I can no more shake the image of shuttle Columbia's astronauts than you can. This third catastrophe brings NASA's death toll to seventeen. And it just dawned on me: One out of every fourteen of the NASA astronauts who've flown have now died in service. The danger facing an astronaut is four times greater than the danger faced by the explorers who signed on with Lewis and Clark.

It's a jolt to realize just how great a risk those people face. Of course they themselves have been quite aware of the dangers. It is you and I who've been lulled into complacency. The word hero, which we too-easily throw about, really does apply.

Risk-taking is a part of any new technology, and I've wondered what might be happening to American technology as we grow increasingly risk-averse. Yet here is a case where we undertook risk and where it cost us dearly.

One person helps me to extract understanding from sadness at this juncture. In 1991, anthropologist Melvin Konner wrote a book entitled Why the Reckless Survive. He posed the question: If recklessness threatens our lives, then shouldn't the reckless suffer Darwinian extinction? Why isn't each generation more risk-averse than the one before it?

He answers his own question. We cannot survive without recklessness. If a parent won't take chances on behalf of a child, the children won't survive. Parents must fight a bear to provide food. They must make a dangerous journey to find habitable land. They must harness fire.

Our Homo Erectus forbears felt no more need for fire in their caves than we did for computers in our homes, back in 1970. Yet a few primitive creatures were reckless enough to claim fire anyway.

Now we're poised, once more, to claim fire for our children. We've heard it argued that we can make weightless experiments, and scan the surface of planets, with unmanned vehicles. So we can and so we surely shall. But this adventure is about something much larger. It's about recklessly grasping the fire of exploration and outreach. We've no more found our final habitat here on the surface of Earth than Homo Erectus did on the plains of East Africa.

Back in 1969, we went to the moon. Ever since, the dream -- and our reckless energy -- has foundered. We've morbidly focused on the morass of earthbound problems and let each one grow more insidious, and we've looked up only when some new fireball seizes our wandering attention. It's time we listened to Shakespeare who said,

O for a Muse of fire, that would ascend

The brightest heaven of invention,

I hope we can reclaim that muse of fire -- methodically and carefully, but with a recklessness of spirit, nonetheless. I hope we can reclaim the legacy that Anderson, Brown, Chawla, Clark, Husband, McCool, and Ramon left us.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Konner, M., Why the Reckless Survive, and Other Secrets of Human Nature. New York: Penguin Books, 1991, pp. 125-139.

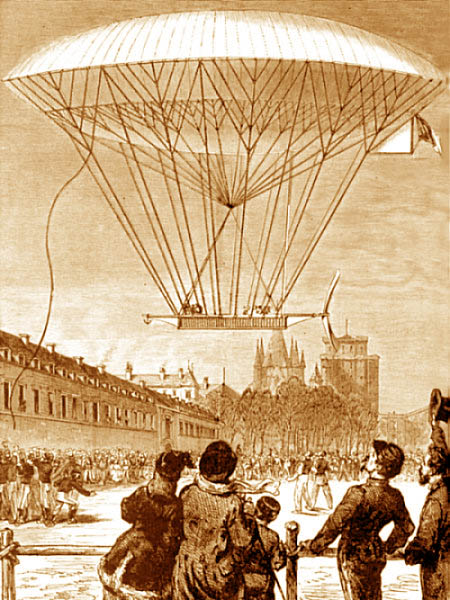

Nineteenth-century Liftoff