Niels Finsen

Today, light and healing. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

The 1903 Nobel Prize in medicine went to Danish doctor Niels Finsen, pioneer of photo therapy. Finsen was only forty-two and suffering from Picks disease, which attacks the internal organs. Born in Denmark, Finsen finished medical school in 1890 in Copenhagen and stayed on to teach for three years. Then he devoted the rest of his life to studying the healing effects of light.

By then, physicists had found that light and heat occupy portions of the electromagnetic spectrum. In the wavelength range from a ten-thousandth of a millimeter to one millimeter, radiation passes from ultraviolet to visible to infrared (or heat.)

And, in the everyday world around Finsen, an increasingly urbanized public had come to believe in the health-giving properties of sunlight, fresh air, and the outdoors. Finsen meant to rationalize modern sun-worship by joining science with anecdote.

He set out to find wavelengths that would best heal the affected skin. He was especially interested in smallpox -- and in tuberculosis, which can attack skin as well as lungs and bones.

Finsen found that ultraviolet radiation (which he called chemical rays) aggravated smallpox lesions, so he filtered it out. The leftover red light sped healing in recovering smallpox victims. But Finsen did use ultraviolet radiation to heal tuberculosis lesions, and he had enough success in that area to win the Nobel Prize.

Finsen had been driven toward light therapy by his own illness. Even before he finished medical school, he'd treated his weakness and anemia by sunbathing. By 1895, he was recommending sunbathing for all forms of tuberculosis, not just skin lesions.

Here he picked up a colorful disciple, a charismatic Swiss doctor and promoter, Auguste Rollier. Rollier opened a whole string of high-altitude tuberculosis sanitariums. Old photos show acres of near-naked bodies arrayed on cots, soaking up ultraviolet rays in the cool bright alpine air. These retreats stayed filled, even during both world wars.

So, where is photo therapy today? Smallpox has (for the moment) been eradicated. And we treat most forms of tuberculosis not with light, but with antibiotics. Few people remember Finsen, and, in fact, he died the year after he won the Nobel Prize.

But he did ease smallpox suffering. The tuberculosis story is not so clear. We now break ultraviolet radiation down into three wavelength ranges. One of them clearly aggravates tuberculosis lesions. Another appears to aggravate some forms and relieve others. So, while photo therapy continues to attract some doctors, controversy nevertheless swirls around it.

As for the general good of sunlight, it might be explained by another recent finding. We now know that bright light eases depression. So of course photo therapy has value. Whatever else sunlight does, it reduces our suffering by making us feel better.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

I am grateful to Margaret Culbertson, UH Art and Architecture Library, for suggesting this topic. My thanks also to Dr. Charles D. Ericsson, U.T. Medical Center, and dermatologist Dr. Jimmy Schmidt for their counsel.

Click here for more in Niels Finsen.

And for material on Rollier see: T. Dormady, The White Death: A History of Tuberculosis, New York: New York University Press, 2000, pp. 157-159.

The form of tuberculosis that Finsen treated with ultraviolet light was called Lupus Vulgaris. (For information on present thinking about photo therapy for regular Lupus -- which is not the same thing.

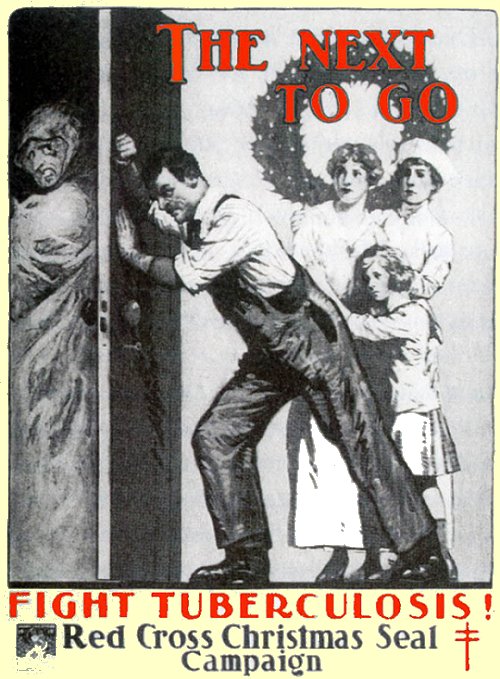

This pre-WW-II, pre-penicillin, poster for Red Cross Christmas Seals captures the hopelessness that we all once felt in the face of tuberculosis.