Camp Cooking

Today, camp cooking and modern times. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

I've come to realize that America was radically altered in the early twentieth century by a particular personality -- someone whom I like to call the Savage Boy Inventor. He was a product of the Arts and Crafts movement, and the Arts and Crafts movement was a reaction to the industrialization of the late nineteenth century. It summoned us back to the manual arts and a more basic way of life.

The Boy Scouts were an outgrowth of that. So, too, were the many books telling young boys that it was manly to take risks, to hunt, and to build their own world in the forest.

It was only a short step from building a forest lean-to to building one's own X-ray machine or airplane. What began as an escape from modern technology soon spawned the greatest technological revolution the world had seen. A mentality of reckless invention underlay our careening development of the new airplanes, radio, automobiles, and everything else that made the twentieth century.

Now historian Abigail van Slyck shows how this process is reflected in, of all things, the institution of camp cooking. Beginning in the 1880s, first the YMCA, then the Boy Scouts, began creating close-to-nature camps, while theorists clucked over the insidious feminization of boys being raised in cities. One noted physician imagined a disorder that he called neurasthenia. He defined it as "a lack of nervous force" in young men.

Summer camps were the answer. And, once in the camp, the matter of preparing and serving food became paramount. Van Slyck talks about the food axis around which camp life revolved. I camped a lot after I finished college, and I still used the early Boy Scout method of baking potatoes in an open fire pit.

Summer camps were the answer. And, once in the camp, the matter of preparing and serving food became paramount. Van Slyck talks about the food axis around which camp life revolved. I camped a lot after I finished college, and I still used the early Boy Scout method of baking potatoes in an open fire pit.

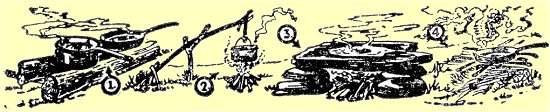

At first, boys cooked their own food and used their knives to eat it off tin plates. But all that set off alarm bells. Most of America had only recently learned elementary table manners. People didn't want their kids losing that hard-gained ground.

Most camps soon went to a system that involved some table decorum in a mess hall. And they moved to a system in which the boys rotated through all the KP chores under the strict hand of the head cook. All this formed a set of male-bonding rituals.

When the Girl Scouts formed, the food axis remained; but talk of cooking over open fires vanished. Girl Scouts cooked on regular ranges -- mimicking the work that awaited a wife and mother. The Girl Scouts also laid heavy stress on principles of household efficiency, just being formulated in the new field of home economics.

In the end, the re-creation of the risk-taking savage had paid off in invention. By the 1930s, most camps were using professional cafeteria service with electricity and refrigerators. Today, van Slyck observes, the very camps that arose in resistance to technology, now teach technology. She smiles at today's "computer camps" -- the natural conclusion of all this, and the ultimate oxymoron.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

A. A. van Slyck, Kitchen Technologies and Mealtime Rituals: Interpreting the Food Axis at American Summer Camps, 1890-1950. Technology and Culture, Vol. 43, No. 4, October 2002, pp. 668-692.

For more on the Savage Boy Inventor idea, see: J. H. Lienhard, Inventing Modern: Growing up with X-Rays, Skyscrapers, and Tailfins, New York: Oxford University Press, in press, expected Fall 2003, Chapters 12 and 13.

All images here were taken from the 1912 Boy Scout Handbook for Boys.