Sinking the Bismarck

Today, we wonder how the Bismarck was sunk. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Some history, right or wrong, is sacred. We pin our sense of self upon it. We don't want it changed. American schoolkids learn that Fulton invented the steamboat in 1807. The fact that a French inventor ran a successful steamboat 24 years earlier is one we do not welcome.

But historical icons do come under attack. Just as medicine only approximates the healing of broken bodies; just as engineers only approximate the perfect machine; history only approximates what really happened in the past. Recent headlines about the 1941 sinking of the German battleship Bismarck show how this works.

On the Bismarck's first voyage into battle, it caught up with the British battle cruiser Hood in the North Atlantic and sank it. Over fourteen hundred British sailors died; only three lived. It was a terrible blow in a war that the British were losing. However, the British had shot a hole in Bismarck's bow, letting enough water in to slow her down.

Bismarck turned back toward France with the British Navy in furious pursuit. They finally caught her in the Atlantic, west of France, and went after her with antediluvian torpedo-carrying biplanes. Most torpedoes missed, and those that hit didn't do much until one torpedo damaged its rudder. After that, the Bismarck became a sitting duck. When she finally did sink, over two thousand German sailors died, and the British managed to rescue only 115 surivors.

This was an enormous morale boost to the British during the darkest days of WW-II. But it was clouded by German survivors who claimed they'd scuttled their ship, thus seeming to blunt Great Britain's victory. So we ignored the scuttling reports when we put the story into our history books; and thus things stood for 61 years.

Then James Cameron, who'd made the movie Titanic, launched an American expedition into the Bismarck wreck. Bismarck was only slightly smaller than Titanic, and it was three thousand feet deeper -- three miles deep! There they found evidence to support the scuttling story. They found torpedo holes, but none seemed to penetrate beyond the protective outer hull. So what had really happened?

Well, toward the end, Bismarck's upper decks were in flames, she could no longer fire her guns accurately, and sailors were leaping from the decks to bob in the water. When Bismarck finally did sink, she sank very fast. The Germans probably did try to keep the burned-out ship from falling into British hands by detonating preset charges on the ship's bottom. But did they speed Bismarck's sinking by minutes or by hours? Who knows? (For that matter, who really cares?)

Yet there are those who still feel that the British victory is tarnished by a German coup de grace. I don't get it, but then I was raised in an American grammar school, not a British one. My concern is with Fulton and that French steamboat -- not with German sailors hastening the Bismarck to her inevitable grave.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Nagorski, A., Spying On the Bismarck. Newsweek, Dec. 9, 2002.

A great deal of material is available on the Internet. You might see also http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Last_battle_of_the_battleship_Bismarck.

I am grateful to three colleagues for extensive helpful conversation concerning this episode: Ralph Metcalfe and Lewis Wheeler, UH Mechanical Engineering Department, and Sarah Fishman, UH History Department.

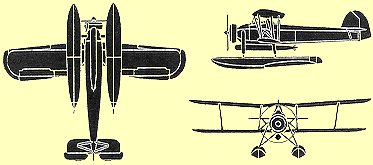

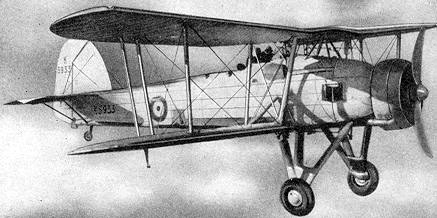

(Images from the National Aeronautics Council, Inc. Aircraft Spotters' Handbook, 1943.)

The Fairey Swordfish Mk II torpedo bomber. Max.speed: 138 mph, Range: 550 miles with torpedo. It is shown equipped with wheels (above) and with pontoons (below). The Swordfishes that attacked the Bismarck were launched from the British aircraft carrier Ark Royal.