The Seashore Test

Today, we hone our ears. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Years ago, I was offered a battery of preference tests to determine what field I should be in. The counselor ran through her list: The Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory, the Graduate Record Exam, and so forth. She also had the Seashore Test, so I asked her to add it to the set.

The test has nothing to do with sandy beaches. It's a test of musical ability devised by psychology professor Carl Emil Seashore. I did well on the test, but there's a great chasm between my ability and that of a fine musician. The Seashore test was used through WW-II, but today it's pretty well fallen out of fashion.

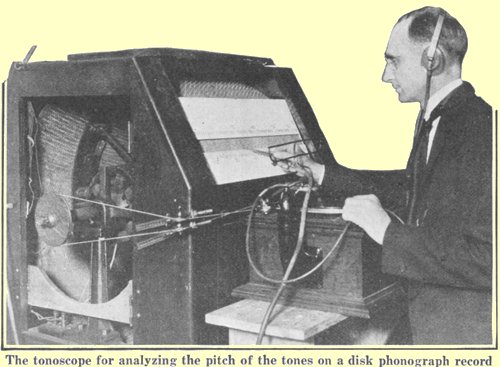

Now here's an article in a 1922 Scientific American. It asks, "Are You a Musician?" It describes the results of Seashore's sixteen years of work on the test. It shows him listening through earphones to phonograph records of sounds. He tests five kinds of musical ability: discrimination of pitches, dissonance, rhythmical figures, and intensity; as well as an ability to remember melodies.

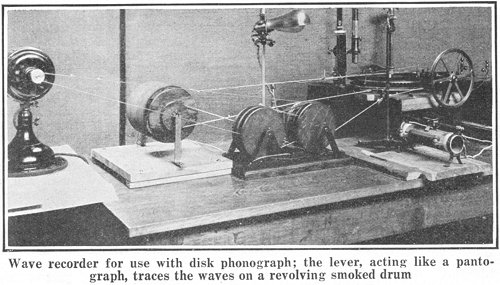

In our electronic age, we're jolted by some of his apparatus. He has to use complex machinery to do what electronics makes so easy today. He's created special motor drives whose speed doesn't vary and systems of pulleys to generate reproducible pitches. He's made a special set of tuning forks.

The article ends with the story of a boy in an Iowa town who wanted to be a violinist. His father wanted him to be a businessman. The father finally let Seashore judge the case. The boy did very well on the test and, according to the article, has now "been hailed by critics as the 'Iowa Kreisler' [while he] came within an inch of being just another Iowa hardware merchant."

But a key fact in that story gets swept under the rug. It is that the boy desperately wanted to be a violinist. Beyond that are also vast dimensions of musicality that'll never show up on a set of one-dimensional measures.

What, after all, is involved in knowing how to shape a musical phrase? Watch any fine musician close-up, and you'll see a cool blue aura of relaxation coupled with a white-hot intensity of focus. Scientific detachment will never capture, say, Itzhak Perlman's vast intelligence, personality, and total immersion in the sound and in its meaning.

Science was exploding into everyday American life in 1922. It took vast sifting for us to learn what science could and could not do for us. We generated every kind of hyperbole and endless false hopes. Out of all that we've finally filtered a remarkable world.

Sound and communication were a great piece of it all. Psychologist and engineer Carl Seashore was only one of thousands who threaded through the complexities of handling sound. I'm acutely aware of that, here in the medium of public radio today -- the winnowing and filtering that has yielded at last this seemingly miraculous convergence of musicians, voices, sounds, and technology.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Cary, H., Are You a Musician? Professor Seashore's Specific Psychological Tests for Specific Musical Abilities. Scientific American, December 1923, pp. 326-327.

Seashore, as shown at work, in the 1922 Scientific American magazine article.