Lardner's Steam Engine

Today, old books with a message for the present. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

The Reverend Dionysius Lardner was the British editor of a huge set of books in the early 1800s. He called his series The Cabinet Cyclopaedia. A part of this, called The Cabinet of Natural Philosophy, included scientific, technical, and general information of all kinds. He and his writers (who happened to include Mary Shelley) wrote for a broad audience of practical readers who would never see the inside of a university -- titles like A treatise on Mechanics or Hydrostatics and Pneumatics.

Let's look at two editions of his Steam Engine Familiarly Explained and Illustrated. The one published in 1824 came out a scant four years after Richard Trevithick built his first demonstration steam-locomotive track in London. No railroads in this edition!

But the 1836 American edition is quite another story. By now, railroads were the newest industry. The technology had quickly crossed the ocean from Great Britain to America, and the builder Mathias Baldwin had already created an American rail industry.

Chapters on railroad engines now appear as suddenly as railroads themselves had done. Lardner even includes advice to potential investors in railroads. (The American editor adds a whole new chapter on steamboats. It has a nice confident ring to it, since we were ahead of England in putting our engines on water.)

The chapter on fuel economy is fascinating. By 1836 fuel consumption had risen alarmingly, and it demanded attention. Natural philosophers were hard at the job of writing the new science of thermodynamics to explain fuel efficiency. Without it, this chapter does no better than to recite clumsy rules of thumb. But that very clumsiness represents need, and that need is shaping a new science.

Lardner's interest in power resurfaces in his book Hydrostatics and Pneumatics. When he speculates on the motive power of liquids and gases, he clearly responds to the power-hunger of the nineteenth century. He talks about the old water wheels. But he seems unaware that -- even as he wrote -- water wheels were being made obsolete by the vastly superior water turbine.

Lardner's books use hardly any math. We read labored verbal arguments that could have been made so simple with just a little algebra or calculus -- with the mathematics that British and American engineers were just starting to study in school.

The book on pneumatics treats the new technology of flight. Hot-air balloons were fifty years old, and parachutes less than that. The book dwells on the unsolved problem of navigating in a balloon -- of taking control of its flight away from the wind and giving it to a person. The first dirigible would appear with that capability just twenty years later.

And so we still learn from these old books. Today, they remind us of the way our lives are being changed by some forces we're able to see -- and by others that are already poised to catch us completely by surprise.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Lardner, the Rev. Dionysius. Hydrostatics and Pneumatics. With notes by Benjamin F. Joslin, M.D. (from The Cabinet of Natural Philosophy, D. Lardner, ed.). Philadelphia: Carey and Lea, 1832.

Lardner, the Rev. Dionysius. The Steam Engine Familiarly Explained and Illustrated, with additions and notes by James Renwick, LL.D. Philadelphia: Carey and Hart, 1836.

Lardner, the Rev. Dionysius. Popular Lectures on the Steam Engine in which its Construction and Operation are Familiarly Explained ... New York: Printed for Elam Bliss, 128 Broadway, 1828. (I do not have a copy of the original 1824 edition.)

Lardner, D., and Kater, H. Treatise on Mechanics. Philadelphia: Carey and Lea, 1831.

This is a greatly revised version of Episode 198.

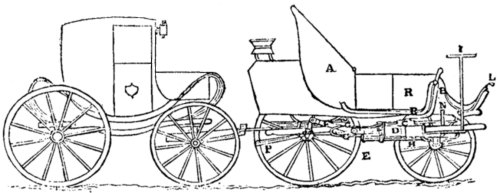

This remarkable image from the 1836 edition of The Steam Engine Familiarly ... is found in the section titled, "Locomotive Engines on Turnpike Roads." It shows, not a steam locomotive but, rather, an embryonic idea of the automobile.

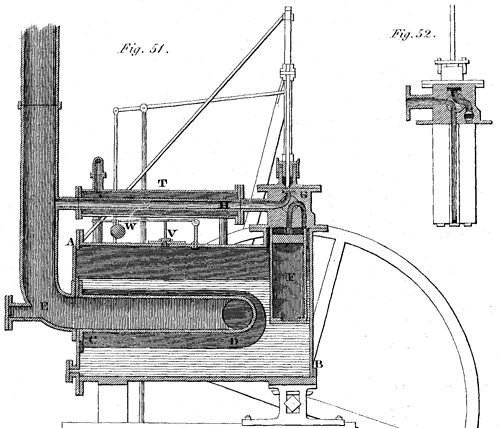

Also from the 1836 edition: An early marine engine and steam boiler.