Eiffel's Towers

Today, Eiffel builds two towers. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Alexandre Gustave Eiffel was born in Dijon in 1832 and trained as an engineer at the Ecole Centrale de Paris. He designed bridges and viaducts in his early life, and he took up architecture later. He was part of a failed French attempt to build a Panama canal in 1893. As a very old man, he turned his ever-adaptable mind to the new technology of the twentieth century -- to flight. He designed one of the early wind tunnels.

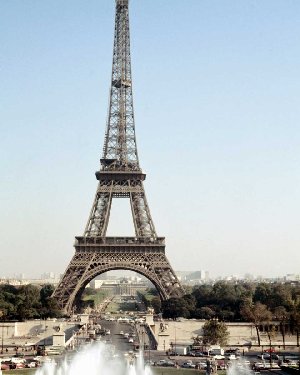

I'd like you to think about a tower he designed that's even more familiar than the Eiffel Tower. But, before I do, let's look at the one that carries his name. He built the wild, seemingly-mad Eiffel Tower for the 1889 Paris Exhibition, and it has marked France to this very day. Who can think of Paris without seeing that pylon rising from its center, one fifth of mile into the air?

Of course, Paris was horrified when it learned what he was up to. A group of famous writers and artists wrote a manifesto against the tower. They said,

We ... protest with all our strength and wrath ... against the erection ... of the monstrous Eiffel Tower ... This arrogant iron mongery [-- this] disgraceful skeleton ... [E]ven commercial America wouldn't want it.

That's not so much short sightedness as it is a reminder that new ideas are alien, no matter how good they are. Eiffel was soon vindicated. Visitors to the fair quickly repaid the costs of building the tower. He was also vindicated in the long run by all of us who, quite simply, regard the tower as beautiful.

In 1887, Eiffel wrote about his intentions. He'd left the steelwork open for the practical purpose of reducing wind loads on the structure. However, he absolutely understood the esthetics of what he was doing. He says,

The curvature of the monument's four outer edges ... as mathematical calculation dictated it ... will give a great impression of strength and beauty.

The remark about "commercial America" in the artists' manifesto was ironic because, five years earlier, Eiffel had designed the huge steel tower inside the Statue of Liberty. The Eiffel Tower, for all its grace, did have a hard commercial side. But Liberty truly symbolized the ideals of both France and America.

The two structures contrast starkly. Liberty, until recently, was the largest statue ever made. She presents a graceful copper shell, but she rides on Eiffel's vast invisible skeleton. Liberty speaks explicitly to the French and American love of freedom. The Eiffel Tower makes no such iconographic appeal. Its purpose is the structure itself -- no more than simple beauty in its own right.

And so Eiffel shifted smoothly between two radically different esthetic aims. It's wonderful enough to've stamped two countries with their identifying monuments. But to've done so in such completely different ways. Well, that truly is magical.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Levy, M.P., Structure and Sculpture. Engineering and Humanities (J.H. Schaub and S.K. Dickison, eds.). Malabar, FL, R.E. Krieger Pub. Co., 1987, Section 3.3.

Barr, V., Alexandre Gustave Eiffel: A Towering Genius. Mechanical Engineering, February 1992, pp. 58-65.

Keim, J. A., La Tour Eiffel. France: Editions "Tel," 1950.

This is a revised version of Episode 189.

Looking down from within the tower, a quarter of the way up

Photo by John Lienhard