Restorative Justice

Today, invention and crime. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Why do we invent? Probably because we so love the rush of being first with a new idea. Invention is freedom; it's pleasure. If necessity drove invention, we'd see far more creative energy focused on those nasty problems that we never manage to solve.

Take crime and punishment: We all want crime to go away, yet despite every existing system of punishment, crime remains. If invention were served by necessity, this is where it would serve us.

A rare exception recently caught my eye. It's the new idea of Restorative Justice. The idea is to focus less on punishment and more on restitution, healing, and rebuilding the community in such a way that the crime won't be repeated. That clearly strikes a nerve: Does it mean letting offenders get away with it? No, Restorative Justice does not mean evading jail with a simple "I'm sorry."

Australia is presently making widespread use of the concept. In a very successful program, juvenile offenders are made to face their victims, to digest the harm they've done, and then to make authentic restitution. The country is clearly feeling its way, but the program appears to be working very well.

A newly-desegregated South Africa had to deal with all the violence that'd gone on during apartheid. They asked, "What's more important, punishing the guilty or healing the nation?"

In an extraordinarily bold move, the new government set up its Truth and Reconciliation Commission. The aim was not the futile exercise of jailing every White who'd ever treated a Black unjustly, or vice versa. It was, instead, a matter of healing years of wounds by identifying wrongdoers and obtaining their amends.

One need only go on the Commission's web site to find hundreds of very convincing messages from South Africans expressing profound regret for the pain they caused during those evil years. Justice, in the sense of an eye for an eye, has not been meted out, and a significant degree of reconciliation has been achieved.

How far can this approach to repairing the damage done by crime be taken? We don't know, of course. But during recent years we've watched Serbs and Kosovars, Israelis and Palestinians, British and Irish, all claiming their pound of flesh in the wake of each new offence. Whether or not Restorative Justice could be made to work in these cases, we don't yet know. What we do know is that conventional responses have only spiraled into chaos.

Such anger, now and then, touches us all. What are we really after when it does? Scalps? I doubt it. We want an end to the damage; we want equity; we want to assuage a victim's pain.

So here's a great rarity, a bold and creative strategy for beginning to address the two things any victim really needs: acknowledgement that a wrong has been done, and restitution. Restorative Justice may or may not be a workable response to crime in the long run. But I bring it up because it's one of the very rare examples in my experience of an inventive response to absolute necessity.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

See the Wikipedia article about Restorative Justice: http://www.aic.gov.au/rjustice/

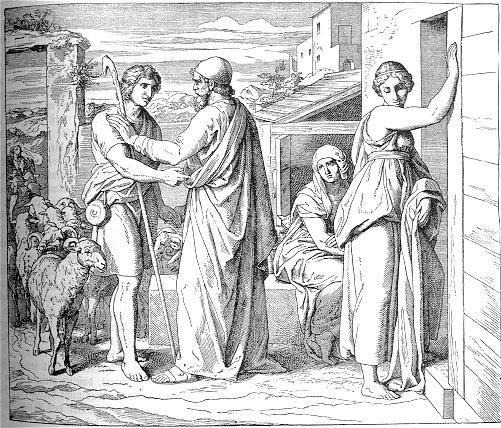

The Reconciliation of Jacob and Esau (from an 1893 German Bible.)