Sewing Machine

Today, the sewing machine. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

span class="dropcap">In the early days of this program, I had an old dot-matrix printer that used accordion-pleat paper. I put the printer on my mother's old floor-model sewing machine -- made in 1905. The sewing mechanism folds down, so I left the top flat to accommodate the printer. The paper sat on the foot treadle below and fed up into the back of the printer. It was all very neat. You'd think the sewing machine had been designed as a printer-stand.

My mother never gave the machine up for an electric model. She liked its movement -- the hand-foot coordination. I liked the florid art noveau design of the cast-iron stand. I liked the grain of the walnut top and the pretty molding. I liked knowing that if push came to shove, I could actually sew with it.

The invention of the sewing machine had to occur after the Industrial Revolution. The production of fabric had suddenly been radically increased. We had more than we ever could've sewn.

So in 1790 an Englishman named Thomas Saint patented the crude forebear of today's machines. For the next fifty years, patent after patent chipped away at the problem of making a machine do the complicated things a human hand does when it sews.

The strongest all-around patent was one filed by Elias Howe in 1846. It led to a spate of thinly-veiled copies and to a patent war. The major inventors finally had to form a sewing-machine trust that paid Howe a handsome royalty. The industrial giant that emerged from this trust was the Singer Company.

My mother's sewing machine was made by the Willcox-Gibbs Company. It was founded around James Gibbs's patent for a chain-stitching machine in 1856. The company was one of many that competed with Singer by making less-expensive machines. It stayed in business at least through the 1960s. In 1859 Scientific American magazine wrote about the Willcox-Gibbs machines. It said:

It is astonishing how, in a few years, the sewing machine has made such strides in popular favor [, going from] a mechanical wonder [to] a household necessity ...

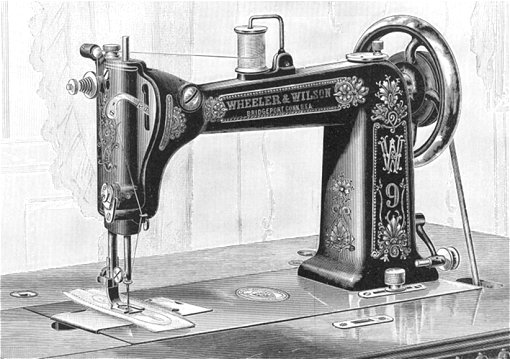

That's what happened. Sewing machines took the country by storm and changed American life. The eight-page section on sewing machines in the 1892 Appleton's Cyclopaedia of Applied Mechanics lists a dizzying array of lock-stitch and chain-stitch domestic and commercial machines. The largest, a sixteen-foot-wide carpet sewing machine, could handle material an inch thick.

When I was six, my mother laid me out on a piece of butcher paper, drew a line around me, and used it as a pattern. She sewed up a human figure, stuffed it with cotton, hem-stitched a face upon it, gave it hair of brown yarn, and clad it in my own home-made clothes. Then she gave me this life-sized alter ego as a playmate.

I look at the old machine and see my mother's quirky imagination, her care for me, her highly-honed mechanical skills. And I remember American home life as it was so powerfully affected by these beautiful and remarkably complex old engines of change.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Cooper, G. R., The Sewing Machine: Its Invention and Development. 2nd ed., revised and expanded. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1976.

Modern Mechanism, Appelton's Cyclopaedia of Applied Mechanics. (Park Benjamin, ed.) New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1892, pp. 790-796 plus plate.

This is a greatly revised version of Episode 167.

The Wheeler and Wilson Sewing Machine

(From Appelton's Cyclopaedia of Applied Mechanics, 1892)