Technology and Communication

Today, technology has something to tell us. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

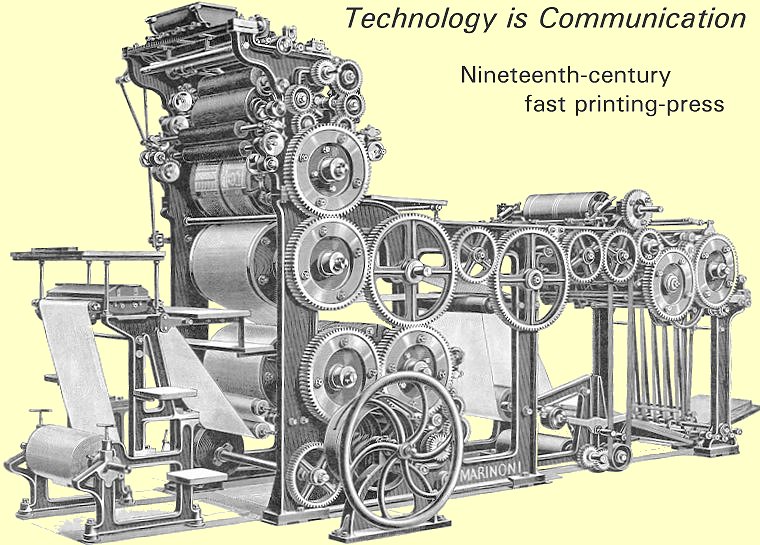

Technology is communication. That fact reveals itself in many ways. Modern humans arose in Africa just over a hundred thousand years ago with a capacity for articulate speech far beyond any other species. They honed that ability at the same time they brought about a great explosion of art and technology. The prime legacy of modern humans was unprecedented self-expression.

Language and technology remain far more interwoven than we might think. Suppose we want to tell a friend how to go from Houston to Detroit. We could write out the sequence of roads and turns she'd take to get there. We might prepare a map. Or we could do something more abstract -- tell her what it feels like to drive to Detroit, about the ride and the sights one sees along the way.

The engineers in Detroit have another way of describing the trip. They design the machine we use to make it. They create the experience of the trip -- give it its form and texture. These engineers use the automobile to tell us their own concept of what that experience should be. The feel of it, the sense of motion, the beauty of the auto, the way the car takes part in our lives and shapes us. These are all things that the designer consciously says to us in a remarkably efficient and compact way.

This was impressed on me some years back when my wife and I found a prefab furniture item we needed. The box had been damaged by a forklift, and the as-is price was next to nothing. It was a big, complicated item, with ten pages of assembly instructions.

This was no job for sissies. But when we opened the box, the instructions were gone. Thirty precut pieces of wood, a couple hundred metal and plastic fittings, and no instructions.

At first I was devastated. Then I realized I could consult the designer directly. I simply looked at the parts and listened to the clear logic they represented. Why was this piece notched and drilled just so? Why did some fittings have little ribs while others didn't? In the end, I was relieved of the tedious intermediary of written instructions. When I worked from inside the designer's head, the whole thing went together smoothly. I walked away with a real respect for this anonymous person whose essential sense of simplicity and elegance I had come to know intimately.

We're perfectly happy to acknowledge other nonverbal forms of communication -- pictures, music, body language -- before we acknowledge technology. Yet technology is the largest such presence in our lives, and it speaks to us with powerful clarity and directness.

Poor technology might well speak of venality and greed. Good technology speaks of beauty, form, and order. That's because the most effective makers and builders of things are not driven by fame or gain. They are driven by the need to share the vision that's formed in their minds. That was true in the Stone Age, and it remains absolutely true today.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

This is a greatly revised version of Episode 187.