Library of Work and Play

Today, we make things. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

It was 1912. The industrial world had produced a flood of domestic products. Beginning in the early nineteenth century, a clutter of cheap plaster statues, kitchen gadgets, linoleum floors, and other imitation elegance had begun piling up in our homes.

It was 1912. The industrial world had produced a flood of domestic products. Beginning in the early nineteenth century, a clutter of cheap plaster statues, kitchen gadgets, linoleum floors, and other imitation elegance had begun piling up in our homes.

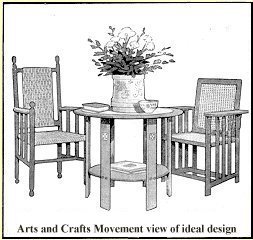

We'd invented the term homemade to summon up what we felt we were losing. As individual craftsmanship began vanishing under piles of manufactured goods, people like John Ruskin and William Morris began the so-called Arts and Crafts Movement. That movement gained momentum in late-nineteenth-century England, and then moved off into other countries. It reached its apogee just before WW-I. Out of it came Frank Lloyd Wright, the German Bauhaus School, and new lean forms of functional design.

In 1912, Cheshire L. Boone published his Guide and Index to the Library of Work and Play -- a ten-book set on arts and crafts for young people. This was a focused effort to bring the ideals of the movement to a generation born into twentieth-century industrialization. We may be mechanized, but Boone insists that,

There was never a time in the history of the world when each race, each nation, each community unit, each family almost, did not possess its craftsmen and artists.

He goes on to identify individualism as the commodity that craftsmanship alone will salvage. He also adds an idea that historians were just beginning to understand -- that the true historical record is to be found in wordless artifacts every bit as much as it is in written documents. (It took another fifty years for that notion to gain wide currency.) Boone also sees, very accurately, how craft serves learning. He says,

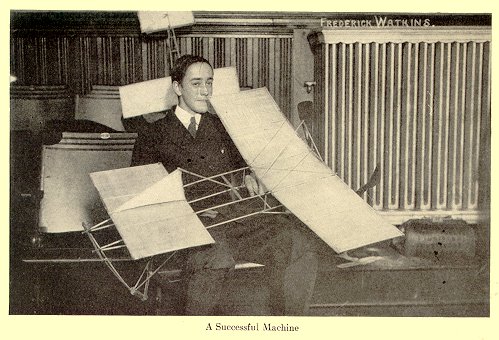

The boy makes a kite, a telegraph outfit, or a sled in order to give to his play a vestige of realism. He seeks to mold the physical world to personal desires, as men do. Incidentally he taps the general mass of scientific facts or data and extracts therefrom no small amount of very real, fruitful information.

Most books of this kind focused entirely on boys, but Boone gives equal attention to boys' and girls' activities. Of course, there's a lot of gender-differentiation: girls do basketry and interior design. Boys build furniture and model airplanes. Gardening could go either way; but this was still the America of a century ago.

So we read the same ideals of individual capability and clean, uncluttered design that guided the new century. Those ideals had become part of my school curriculum by the 1930s. Some of the Arts and Crafts Movement was retrograde, of course -- nostalgia going nowhere new. But here the movement wraps its arms around new technologies. We're asked to build our own radio or steam engine. Boone strongly emphasizes model-airplane building only nine years after the Wright Brothers flew. No retrograde Romanticism here.

At the heart of the Arts and Crafts movement was a call to enter the twentieth century with our heads screwed on. Factories and high technology were an obvious fact of life. But they were not any reason for giving up beauty, elegance, and hands-on involvement with artifacts. Here that message comes, with wonderful intensity, to the generation that built the remarkable twentieth century -- the world that you and I were given at our birth.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Boone, C. L., The Library of Work and Play: Guide and Index. Garden City: Doubleday, Page & Company, 1912.

Do take a moment to click on the links in the posted script above to see many of the illustrations from Boone's fascinating book. (The two illustrations shown here are also from Boone's book.)