Science in 1904

Today, a bright new century. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

I refer to the bright new twentieth century, not the twenty-first. A 1904 issue of The Literary Digest helps to usher it in. The section of the magazine on politics analyses the postal scandal, lynchings in Ohio, Indian land scandals, and William Randolph Hearst's bid for the Democratic presidential nomination.

I refer to the bright new twentieth century, not the twenty-first. A 1904 issue of The Literary Digest helps to usher it in. The section of the magazine on politics analyses the postal scandal, lynchings in Ohio, Indian land scandals, and William Randolph Hearst's bid for the Democratic presidential nomination.

In the section on letters and art we worry about the declining taste for poetry, and we ask what makes a book sell. We hope that Henry James will return to America from England. We identify Dostoyevsky as the dominant force in Russian literature.

The section on religion is suspicious of Catholics and Mormons, supports missionary work, and is shocked by the Episcopal bishop of Arkansas whose racist writings show how we were drifting in the years before WW-I. (His own church comes back at him, telling him he needs to look at Booker T. Washington and the Tuskegee Institute.)

And so we catch a glimpse of America entering the last century and taking the measure of things, just as we try to do today. It was an America skidding toward race riots and war. But it was also an America about to be turned on its ear by new art, new literature, and the formative agency of radical new science. It was a world being reinvented as no other new century had ever been.

This Literary Digest does not miss the role that science and technology are playing. Where are the Wireless Telegraphs? cries a headline. In 1901, radio pioneer Marconi had received a signal of three clicks, which may or may not have actually crossed the Atlantic. After that, hope and expectation raced ahead of invention.

A scant twenty-seven months after Marconi, the article laments that radio hasn't yet been put to use. Just twelve years later, it seemed perfectly reasonable to expect a young lad to build his own radio for a Boy Scout merit badge in wireless telegraphy.

A scant twenty-seven months after Marconi, the article laments that radio hasn't yet been put to use. Just twelve years later, it seemed perfectly reasonable to expect a young lad to build his own radio for a Boy Scout merit badge in wireless telegraphy.

Another article announces the discovery that Antarctica is actually a landmass under all the ice. It's been deceptive, because the huge ice packs extend out over the shoreline and into the sea.

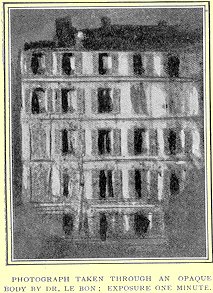

But the truly remarkable item in this domestic magazine is one on radiation. Two photos, one of a building and one of a flame, have both been taken through an opaque wall using some form of radiation -- probably akin to X-rays. The writer pieces together what various scientists have been saying to explain radiation.

By now, scientists see that the atomic structure of matter -- of, say, radium -- changes as it radiates. They also suspect that matter turns into energy during radiation. A year later, Einstein would write e = mc² and quantify that idea. But this is a year before special relativity, and here this literary magazine tells us:

Matter, hitherto regarded as inert and able only to give up energy that has been furnished to it, is, on the contrary, a colossal reservoir of forces. ...

What a time that was to've been alive!

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

The Literary Digest, New York: March 10, 1904, p. 393-430.

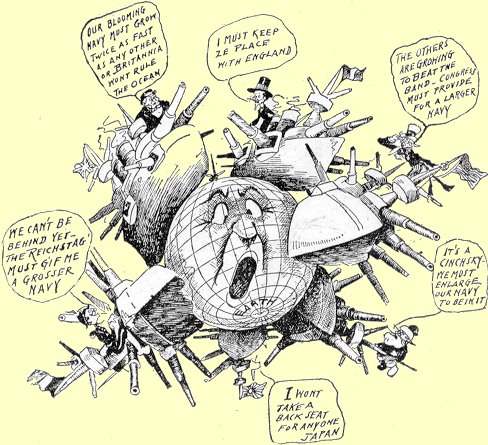

Literary Digest cartoon expressing concerns that we share today.