Last Days of Pompeii

Today, we visit Pompeii. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

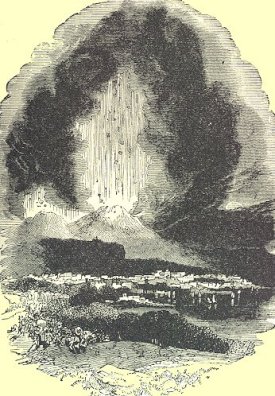

I was only five one day when my parents took me off to the Uptown Theater on Grand Avenue in St. Paul, Minnesota. We went to see The Last Days of Pompeii. Basil Rathbone played Pontius Pilate, before he became typecast as Sherlock Holmes. The primordial special effects in that early talking picture raised the hair of this little boy. Vesuvius erupting -- fire and lava consuming the corrupt citizens on that terrible day of August 24, in AD 79.

I was only five one day when my parents took me off to the Uptown Theater on Grand Avenue in St. Paul, Minnesota. We went to see The Last Days of Pompeii. Basil Rathbone played Pontius Pilate, before he became typecast as Sherlock Holmes. The primordial special effects in that early talking picture raised the hair of this little boy. Vesuvius erupting -- fire and lava consuming the corrupt citizens on that terrible day of August 24, in AD 79.

Pompeii is interesting precisely because it was not flooded by lava. Rather, it was covered over with volcanic ash and some mud. Just as Spirit Lake was obliterated by ash and mudslides when Mount St. Helens erupted, so too was this model city of twenty thousand people. Two thousand Romans died of asphyxiation and were entombed in ashes until the city was rediscovered in 1748. The nearby town of Herculaneum suffered far greater material destruction. It was flooded by boiling mud. Art and artifacts were destroyed. Its ruins were encased in hard clay.

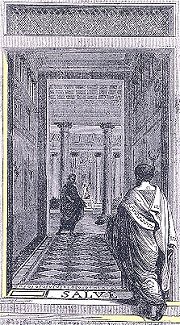

Scholars and artisans have worked on Pompeii, restoring and rebuilding it. Now you and I can walk the streets of a Roman city. And there's a curious wrinkle here. A decade before the eruption, a warning earthquake had laid Pompeii in ruins. For ten years, its citizens had rebuilt their city into a model of urban renewal. What we find beneath the ashes is state-of-the-art, first-century Roman construction along with a great trove of fresh art -- all remarkably preserved.

Scholars and artisans have worked on Pompeii, restoring and rebuilding it. Now you and I can walk the streets of a Roman city. And there's a curious wrinkle here. A decade before the eruption, a warning earthquake had laid Pompeii in ruins. For ten years, its citizens had rebuilt their city into a model of urban renewal. What we find beneath the ashes is state-of-the-art, first-century Roman construction along with a great trove of fresh art -- all remarkably preserved.

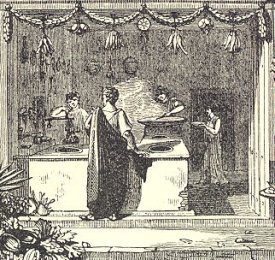

This lovely city, so gracefully and beautifully restored, has become cold news. During the 1960s, people fixated on some erotic art that turned up in a few of the buildings. Once I overcome the image of flames washing over some Hollywood Babylon, up on the silver screen of the Uptown Theater, I realize that Pompeii is closer to our reconstruction of Williamsburg, Virginia. That's why I'm so taken with an old book I was recently given. Called A Museum of Antiquity, it was written in 1882, and it devotes over a hundred pages to Pompeii. It takes us through houses of real people with real names.

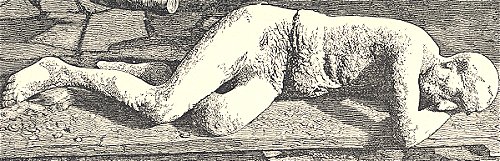

We visit the baker's shop, the wine merchant, and fast-food diners along the streets. Mud had solidified around some bodies, long since turned to dust. They became clay casts from which a few citizens and animals have been recreated in plaster. Later scholars have corrected some details in this old book, but that misses the point. For Pompeii isn't so much about history as it is about the continuity of life.

What we find here is no Babylon, no theater set of an imagined past. It is, instead, the world you and I live in, a world of upscale shops and theaters, much like Grand Avenue in St. Paul today.

What we find here is no Babylon, no theater set of an imagined past. It is, instead, the world you and I live in, a world of upscale shops and theaters, much like Grand Avenue in St. Paul today.

Pompeii was a town where ordinary and hardworking people lived the good life until an unlikely instant when they ceased to live at all. My Uptown Theater no longer exists, but Pompeii does. And, so too, does our own ongoing hope as we work to build the good life in our towns -- in Houston and St. Paul, in Norwalk and Durango.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Bulwer-Lytton, E. The last days of Pompeii. New York: Heritage Press, 1957. (The original publication date was 1835.)

The movie version I mention was: The Last Days of Pompeii, RKO, 1935, starring Preston Foster and Basil Rathbone.

Yaggy, L. W., and Haines, T. L., Museum of antiquity: A description of ancient life. New York: Standard Publishing House, 1882, pp, 117-112. (I am grateful to Andrew Lienhard for this wonderful old travelog of the ancient world.)

The old Uptown Theater lay on the north side of Grand Ave. in St. Paul, between Lexington and Oxford. It has long since been torn down and replaced with another business. I mention this in deference to Minneapolis listeners, who still have an Uptown Theater of their own.