Houston Traffic, 1924

Today, Houston's traffic in 1924. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

I was recently given a report that'd oddly turned up in some old files at Cooper Industries. It'd been prepared for the city of Houston by a traffic-light salesman in 1924. It begins like this:

In any growing city of [over] 50,000 ... certain traffic practices [are] the outgrowth of a course of least resistance [from days] when little attention was paid to how fast a man's horses were driven or how he tied up at the ... hitching rack.

He goes on to point out that downtown Houston traffic has become a mess. Greater Houston would eventually grow to 4.3 million people -- some thirty times the 1924 population. And, while our present traffic is bad, it's easier to get around now than it was then.

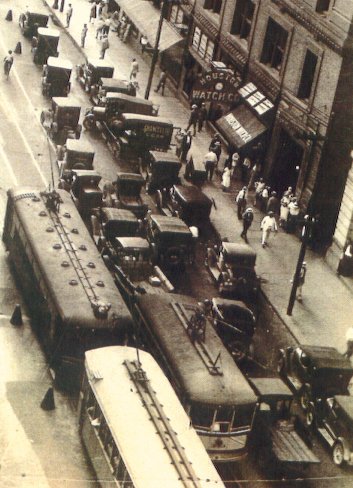

The salesman sees why we had traffic problems. We'd expected to have the same freedom of mobility that we'd had on horseback. He includes nineteen wonderful old photos of downtown traffic. They provide a perfect time capsule of an age just beyond the horse and buggy; yet not one horse remains in the pictures.

Electric trolleys had come to Houston 1891, long before the automobile, and they appear in almost every picture. But cars and trucks now clutter the streets, threading their way through the rows of trolleys.

Americans certainly intended cars to be the new agents of free mobility. And, at first, we used them with cowboy indifference to the need of a high-density population. The pictures show them parked both parallel and perpendicular to curbs. They're double parked, they're parked at an angle, they even sit on sidewalks. Anyone "in the know" had a police courtesy card. And you could park all day on a city street. Trucks often sat idle on the street for days.

The number of cars in Texas had increased by a factor of twenty in a ten-year surge. The first traffic policeman had been stationed in a downtown intersection only three years earlier. The new electric traffic signals had yet to reach us.

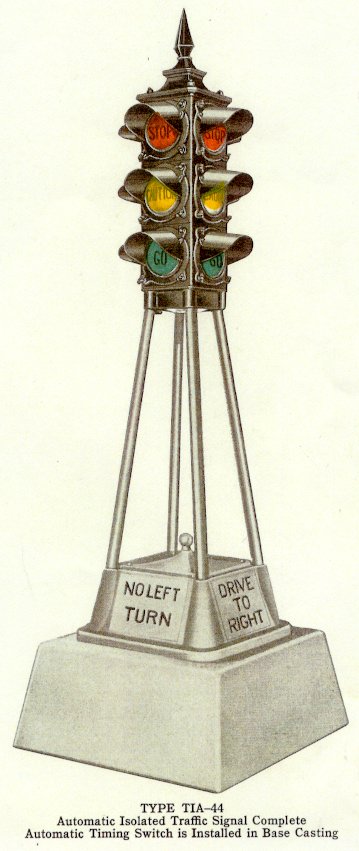

The traffic-light salesman who wrote this utterly convincing report worked for the Crouse-Hinds Company. He includes their brochure. The top of the line is the Automatic Isolated Traffic Signal. It's a three-color light mounted on a stand in the middle of the intersection with an automatic timing switch in the base.

How we finally got traffic under some semblance of control is another story for another day. But the struggle between personal freedom and our communal best interest still rages around the automobile. Should we be allowed to use cell phones as we drive? Must we wear seat belts? What about exhaust emissions?

I look at those old photos and realize what a major effort of the inventive muse is needed if we're to have elbowroom without having my freedom limit your freedom. It seems hard to believe the level of traffic density that we now handle routinely, once we've seen those old streets seeming to choke on Model-T Fords.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Improper Regulation of Traffic in Houston and Suggested Changes. (Brief informal report. No author is given. A Crouse-Hinds Company brochure dated 1924 is attached.) I am grateful to John Breed of Cooper Industries for providing the report.