The Medical Genius

Today, we measure how far we've come. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Not until after the Civil War did the germ theory of disease begin falling into place. We didn't have effective means for fighting microbes until long after that. Anesthesia was used only now and then during the Civil War. Dentists drilled my teeth for ten years before I first had the relief of Novocain.

The medical practice we enjoy is remarkably recent: antibiotics, polio vaccine, most surgical techniques, modern painkillers. Cancer has only recently become less than a death sentence.

Now I hold the 1892 edition of a book first published in 1887. The author, a Dr. Stacy Jones, entitles it The Medical Genius. In his preface he says,

[The] purpose of this book is to exhibit the pure genius of our best drugs; as attested by the undoubted cures effected by them in doses both minute and massive.

This three-hundred page encyclopedia of remedies is organized by agents: Acacia, Aconite, Alcohol ... each followed by the cures it will bring about. Alcohol is recommended for sore throat, itch, tooth decay, bedsores, angina, and spotted fever.

The A's continue: Ammonia, Arsenic, Antimony. The B's include Belladonna. Cabbage will draw the infection from a wound, and Chloride of Chromium will cure external cancers. Coffee grounds sprinkled on live coals will clear out atmospheric impurities.

Hemp is recommended during tooth extractions. (And now contemporary advocates are fighting for the use of marijuana as a painkiller.) Certain pains might also be allayed with a tea made from live honey bees. Myrrh is recommended for a sore throat and Opium for Puerperal Fever -- as well as for a drunken stupor.

We find Pepsin, Potash, Silica, Silver, and Starch. And when the alphabet runs out, a section tells us that Electro-Magnetism will heal headache, delirium, baldness, poor eyesight, deafness, pneumonia, and cancer. It will even help broken bones to knit.

Another section, entitled Hints, tells us how to diagnose death. (Place the end of the patient's finger in an open flame. If the blister contains liquid, the patient is still alive.) It also tells how to prepare an anesthesia. (Mix one part chloroform with three parts ether and two parts alcohol.)

I suspect that we might gain much by combing this old book to find herbal remedies that contain useful agents. And much of the book offers valid common sense. But so much more is terrifyingly wrong. I've read many other such books -- enough to know that Dr. Jones was not a quack. He really represented the state of medicine just over a century ago.

Historians aren't supposed to talk about progress. For progress is so often illusory. But I put this book down in a state of complete amazement at how much sheer progress medicine has made in little more than my own lifetime.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Jones, S., The Medical Genius. Philadelphia: John C. Winston & Co., 1887/1892.

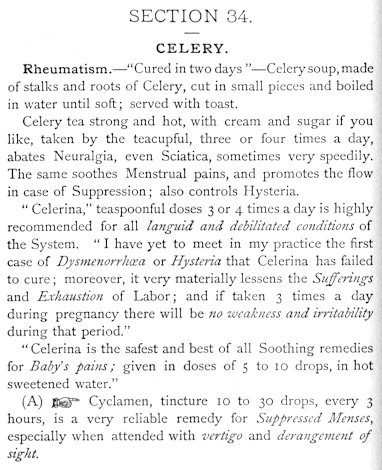

A typical page from The Medical Genius