Elisha Gray and Miracles

Today, a telephone inventor talks about miracles. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

I always get into trouble when I mention the invention of the telephone. Everyone has a champion with a less successful telephone before Bell: the German Reis, the French Bourseul, the Italian Meucci, and many more. One was the American Elisha Gray.

On February 14, 1876, Gray filed a caveat with the U.S. patent office for his telephone. Unfortunately for him, Bell had filed his own patent just hours earlier on the same day. Bell formed the Bell Telephone Company, while Western Union acquired Gray's patent. The resulting patent war was one of the bloodier ones on record.

On February 14, 1876, Gray filed a caveat with the U.S. patent office for his telephone. Unfortunately for him, Bell had filed his own patent just hours earlier on the same day. Bell formed the Bell Telephone Company, while Western Union acquired Gray's patent. The resulting patent war was one of the bloodier ones on record.

So much is written about Bell. Perhaps we should become better acquainted with Gray. Gray was born in Ohio in 1835. He worked as a blacksmith, as a boat-builder, and as a carpenter. At twenty-two, he went back to finish high school, then to do a two-year science degree at Oberlin. He earned his way with carpentry.

Gray's first patent, five years later, was for a new telegraphic relay. He'd soon created the Western Electric Company as a subsidiary of Western Union. He went on to conceive his telephone. He lost the resulting patent war, but he kept on inventing. In the end, he probably made more money than Bell did from his own subsequent telephone patents. He also patented an early fax machine.

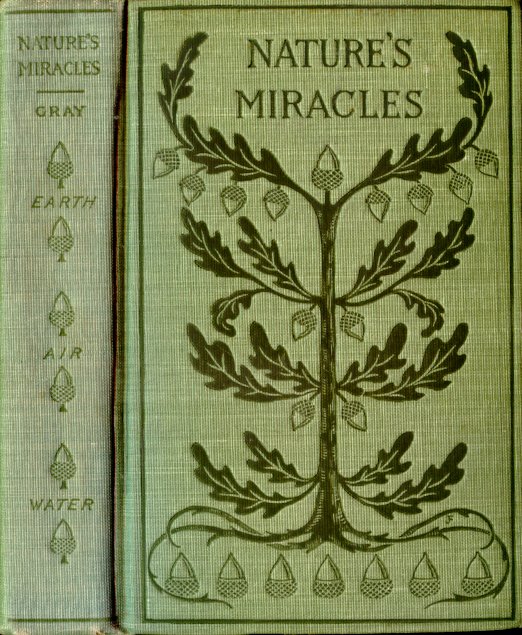

But my present interest in Gray is not in his inventions. It is in an astonishing item I found at a used bookstore. Gray's book, Nature's Miracles, is the first of a three-volume set that he completed the year before he died in 1901. This first volume deals with earth, air, and water. Gray opens with this telling remark:

Some may claim that is it unscientific to speak of the operations of nature as "miracles." But the point of the title lies in the paradox of finding so many wonderful things ... subservient to the rule of law.

The nineteenth-century science-religion wars had reached their worst, and Gray was having no part of the nonsense coming from extremists on both sides. He was deadly serious about using the word miracle in its religious sense. He insisted that the universe is the result of intelligent design. But he also insisted that the real miracle is that all things remain obedient to natural law.

On the matter of origins, he quotes Genesis, "In the beginning, ... ." Then he adds, "Whatever our speculations may be in regard to a 'beginning,' and when it was, it is written in the rocks that, like the animals and plants ... , the earth itself grew." He mirrors that practical view of facts in another remark: "The man who is all theory is like 'a rudderless ship on a shoreless sea.'"

So we catch a glimpse into the process that made one great inventor. Gray's life was constant evolution: from carpentry to electrical devices, to great inventions. And, finally, he looked at a universe that he never doubted was invented by God. However, it was a universe whose wonders, like his own inventions, I suppose, were all "subservient to the rule of law."

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Gray, E., Nature's Miracles: Familiar Talks on Science. Vol. I: World-Building and Life, Earth, Air, and Water. New York: Fords, Howard, & Hulbert, 1899.

See also the biographies of Elisha Gray in American National Biography, The Dictionary of American Biography, and The National Encyclopaedia of American Biography.