Advice for Living, 1836

Today, we learn how to live our lives -- in 1836. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

The nineteenth century gave us any number of books on how to live our lives -- precursors of today's self-help literature, I suppose. Here's a fine example: Dr. Caleb Ticknor's book, The Philosophy of Living. Ticknor's recurring focus is on diet. He begins with eating practices around the world. He concludes that we're a truly omnivorous species; we do equally well as carnivores or as vegetarians. At length, when he gets around to giving advice, his prejudices about food emerge.

He deplores European food as undercooked and over-seasoned. Good digestible food should be thoroughly boiled and bland. He has very harsh words for his contemporary Sylvester Graham -- the man who invented the Graham cracker and promoted brown grain. Bran, Ticknor says, can't possibly contain nutrients. Not until a century later did we learn that bran is what gives us our Vitamin B-1.

Ticknor tries to bolster his claims about diet by quoting a few ideas from the work of William Beaumont. Beaumont was a fine surgeon with a patient who'd been gut-shot in a shotgun accident. When the wound failed to heal completely, Beaumont hired him as an experimental subject and spent several years doing the seminal study of digestion through the hole in the fellow's stomach.

Ticknor does better in a section with the deceptive title, "On the Great Pleasure and Benefit of Using Tobacco." What he does is to systematically show that tobacco is a powerful poison. He points out that nicotine can be used as a muscle relaxant, but a slight overdose will cause paralysis and death. He goes on to talk about child-rearing, education, the role of climate, and marriage. In a section entitled Sex he explains the roles of males and females:

Each [sex], he says, has its proper station. ... Woman is designed to lead a quiet, domestic life ... to watch over helpless, infant innocence: man ... is made to lead an outdoor life, ... to bear the heat and burden of the day.

That was simply common doctrine. It could hardly be called chauvinism. It was a view that almost no one would've questioned.

Ticknor's Preface explains why he's writing this book. The world has grown degenerate. He's surrounded by fanaticism on one side and moral decay on the other. America needs a voice of sanity in a sea of extremism. That, of course, is what writers have said ever since Socrates. Each generation launders its own childhood as it grows increasingly aware of wrongs that've always been there.

Ticknor talks about improper entertainment, about the threat of the imagination and the ailment of idiosyncrasy. He wants us all to live temperate, moderated lives (like his own, I suppose).

All around him, America was exploding in a creative revolution unlike any before it. We were an immoderate, boisterous, brash, and unfettered people in 1836. Our America was built on exactly the attributes that drove the sedate Dr. Ticknor to write this self-help manual on how to escape our own excesses.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Ticknor, C., The Philosophy of Living. Or, the Way to Enjoy Life and Its Comforts. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1836.

Ticknor does not identify Sylvester Graham by name, though he clearly refers to him. In fact, a contemporary reader has penciled Graham's name into the text wherever Ticknor takes a swipe at him.

Ticknor's title page

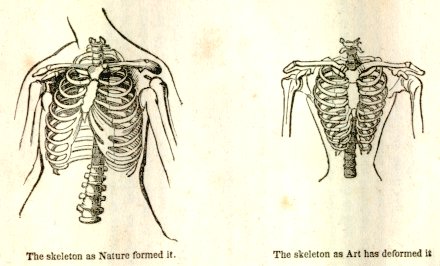

Ticknor's only illustrations deal with the folly of women's tight corsets.