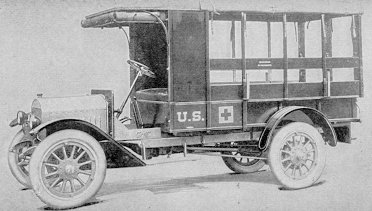

1st Red Cross Ambulance

Today, we ask how to care for a wounded soldier. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

We're in the Smithsonian Institution. We see an odd item. It looks like an old Western chuck wagon with its canvas top and squarish shape. It has a small red cross painted on the side.

This wagon is important. To see why, we go back to Solferino, Italy -- to a little-known battle in a little-known war in 1859. After the battle, a young Swiss named Jean Dunant worked with other bystanders to help thousands of wounded French, Italian, and Austrian soldiers. He wrote a book about that ghastly experience and used it to call for the creation of an international group to give relief in war. The world responded by creating the International Red Cross in 1863.

A few years later the German army started painting the Red Cross symbol on horse-drawn ambulances. But historian Herbert Collins tells us that the Red Cross first provided its own ambulances in the Spanish-American War.

When Cubans revolted against Spanish domination in 1897, Clara Barton -- head of the American Red Cross -- asked President McKinley to help her raise public money for Red Cross relief to Cuba. The government finally joined the effort, but only after the conflict had turned into the Spanish-American War in 1898.

The Red Cross raised $36,000. Most of it was spent on eleven mule-drawn ambulances. Each carried four stretchers and a water cask under the driver's seat. Two of the stretchers could be mounted as bench seats inside. The ambulances were made by the Studebaker company -- before it began making automobiles.

Only two of the eleven ambulances saw action. Those were ones that had gone, not to Cuba, but to Puerto Rico. And they were very useful there. Later, Clara Barton found that the Army hadn't even unloaded the six that were shipped to Cuba.

Two more ambulances were used in New York City, and one saw service with the Army at Camp Thomas, Georgia. It was sent back to Clara Barton in Washington after the war. Eventually a vegetable peddler bought it. The Smithsonian finally located it in 1962. When they restored it, they found that it had originally been painted Prussian blue and chrome yellow.

You might not see anything special when you first look at this simple ambulance. But then its meaning comes clear. You see Jean Dunant's flash of ingenuity after the suffering at Solferino. You see Clara Barton's organizational ingenuity. This humble little wagon represented the first real action by a world relief organization that owed nothing to national interests.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Collins, H. R., Red Cross Ambulance of 1898 in the Museum of History and Technology. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1965.

This episode has been greatly reworked as Episode 1628.

A "modern" ambulance as pictured in the 1923 Wonder Book of Knowledge