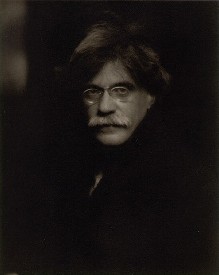

Alfred Stieglitz

Today, Stieglitz and photography, art and reality. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

The person who did most to bring photography into America's artistic mainstream was Alfred Stieglitz. Stieglitz was born in Hoboken, New Jersey, in 1864. But his businessman father raised him both in Germany and in New York City. At eighteen, he went to study mechanical engineering at the Berlin Polytechnic University, whose faculty included the great physicist, Helmholtz.

But Stieglitz's intentions derailed a year later when, on a lark, he bought a primitive box camera. After that, he became increasingly distracted from engineering. He finally switched to process chemistry and dove into the technical side of photography.

Within a few years, Stieglitz had won European prizes for his pictures, and, in 1890, he returned to America. By the turn of the century, he emerged as the center of a New York movement called "The Photo-Secession." The simple aim of The Photo-Secession was "to advance photography as applied to pictorial expression."

So the relation of the camera to painting and sculpture became Stieglitz's central concern. As he struggled to define a legitimate place for art photography, he was quite clear on one point: Painting and photography were two distinct and different forms.

Since modern art sought out new realities, he said, painting would go where photography could not follow. In fact Stieglitz took that as a constraint. Once we begin altering photographic images by hand, he said, the result is no longer photography. I expect he would've cringed at what we do with digital images today.

In 1905, Stieglitz and The Photo-Secession opened a gallery at 291 Fifth Avenue. The 291, as it was called, became a center and arbiter of art in general, not just photography. Stieglitz began to assert his profound understanding of the changing face of art by exhibiting the major new art movements at the 291. Between 1908 and 1911 he and photographer Edward Steichen exhibited Matisse, Toulouse-Lautrec, Rodin, Cézanne, and Picasso as well as photographs.

In 1905, Stieglitz and The Photo-Secession opened a gallery at 291 Fifth Avenue. The 291, as it was called, became a center and arbiter of art in general, not just photography. Stieglitz began to assert his profound understanding of the changing face of art by exhibiting the major new art movements at the 291. Between 1908 and 1911 he and photographer Edward Steichen exhibited Matisse, Toulouse-Lautrec, Rodin, Cézanne, and Picasso as well as photographs.

Stieglitz's efforts were building toward the most famous art show of them all, the 1913 Armory Art Show. A group of young rebels finally organized a huge show and rented an armory to display it. This was no piecemeal exhibition. Now America could see the whole parade of modern art, and, while Stieglitz had not been the organizing force, he'd certainly been the soul of the exhibit.

The Stieglitz we read about, with his turbulent marriage to Georgia O'Keeffe, lived later. By then, we'd begun to see how far reality had been bent by modern physics -- by quantum mechanics and relativity. It took the younger Stieglitz, the one who wouldn't tamper with the eye of his camera, to recognize that Picasso and Braque were being just as literal with their paintbrushes. Stieglitz seemed to realize that what was shifting under our feet in 1903 was not art at all, but reality itself.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Newhall, B., The History of Photography: From 1839 to the Present Day. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1964, Chapters 8 and 9.

Lowe, S. D., Stieglitz: A Memoir/Biography. New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, 1983.

Whelan, R., Alfred Stieglitz: A Biography. New York: Little, Brown and Company, 1995.

America & Alfred Stieglitz: A Collective Portrait. (Edited by Waldo Frank, Lewis Mumford, Dorothy Norman, Paul Rosenfeld, and Harold Rugg) New York: Octagon Books, 1975.

Bry, D., Alfred Stieglitz: Photographer. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1965.

Stieglitz's photo of the Flatiron Building, 1903