Specialized Language

Today, the quotidian denominator. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

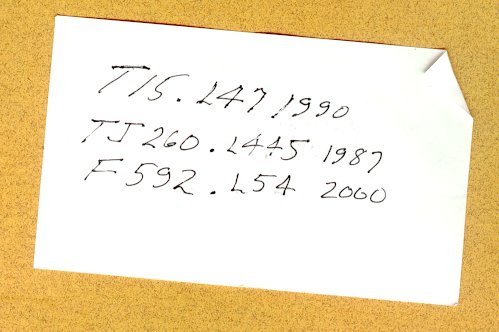

I asked a reference librarian if he had one of those little three-by-five pieces of paper so I could write down a catalog number. (Those slips are usually found on the counter in small wooden boxes, along with short pencils.) He took mock offense: "Please, John, those 'little pieces of paper' have a name; they're called P-slips."

That arcane fact, unknown even to many librarians, set me to thinking about specialized words. When someone in an on-line library discussion asked, "What do you call a ribbon, attached to the spine of a book, for marking pages?" the debate lasted two days. They finally settled on the improbable word, signet. Then someone said, "Why don't you just call it a ribbon page-marker?"

We engineers are every bit as guilty of this arcanery as librarians and doctors -- literary critics and lawyers. I know engineers who'll go to war over the difference between centripetal and centrifugal force. Swing a rock on the end of a string, and you can name the force in the string by whether you regard it as pulling on the rock or pulling on your hand.

I do that with the word heat. I cringe when someone says that a teakettle contains heat. Heat is what we call the energy flowing from the stove to the kettle. Once in the water, it becomes internal thermal energy. That nicety is useful when we write energy balances, but it's of precious little use in the world at large. A dentist talks about the lingual and buccal sides of a tooth -- more terms that few of us need. You and I simply add a few words. We refer to the side of the tooth facing into, or out of, the mouth.

It should all come down to practical utility. When a dentist and technician spend the day locating flaws in peoples' teeth, a word like buccal saves a lot of time. But trying to name every thing in the world would clutter language unbearably.

Years ago, I had a wise, but quirky, professor who was death on verbal clutter. When he came to the ratio of transport properties called the Prandtl Number, he avoided the term. He just squandered two extra words and named the properties. That way, students never got the ratio wrong.

Writing for radio exposes how needless specialized language can be. If we really understand what we mean to say, we can find our way back to plain English. Rarified language makes a fine shield when we're uncertain. Take the word quotidian. In medicine, it means daily or recurring. But it can also mean common, everyday. When I hear someone use it that way, I know I'm being warned not to question. I'm being told that nothing is common, or flawed, about anyone grand enough to use that uncommon word.

So, when I think I have a new idea, I remind myself that I have to put it in words that we all understand. If I can't, I need to keep working. No idea is ever within our grasp until we can tell it in words that we all understand.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

The UH Reference Librarian was Dr. John E. Fadell, linguist and source of limitless word lore. I am also grateful to the good people in the office of Dr. Phyllis Morgan, who, while they work on my teeth, willingly tell me what their words mean. The on-line library discussion group is ExLibris.

Just for the record, the Prandtl Number, Pr, is the viscous diffusivity divided by the thermal diffusivity. It helps one to see whether viscous drag or heat flow is the dominant process in a given problem.

Connecticut listener David Faile writes with one on the more far-out naming stories. It turns out that those removable strips of paper on the outside of the old tractor-feed paper supplies were called perfory. After this episode was first aired (just before the 1999 presidential election) another related term has become commonplace -- the term chad.