Pluto (The Planet)

Today, we discover Pluto. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Before we had telescopes the solar system held only six planets: Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. Long after the telescope there were still only six. Galileo spotted Neptune with his telescope in 1612 but didn't realize it was a planet. William Herschel saw another wandering star in 1781. It took a while, but he finally realized it was a seventh planet. He called it Uranus.

Accurate measurements of Uranus' orbit eventually revealed that it was being influenced by another even more distant planet. European astronomers found that one in 1846. They called it Neptune. Meanwhile, the search for planets was being muddied by asteroids that were showing up between Mars and Jupiter.

Then an even closer study of Uranus' orbit suggested yet another planet outside Neptune's orbit. A young astronomer named Clyde Tombaugh finally found it in 1930 -- a tiny little speck seen through a thirteen-inch lens. It was Pluto -- some three billion miles away, with a diameter only two-thirds that of our moon.

During the 1990s, Pluto's status as a planet was seriously called into question by the discovery of another belt of small objects between Neptune and Pluto. None of these so-called Transneptunian Objects is nearly as large as Pluto. But Pluto, with only one five-hundredth of Earth's mass, is still so small that many astronomers want to call it Transneptunian.

Then a 1978 discovery gave Pluto a unique place among orbiting bodies. What we took to be a single planet turned out to be two nearby planets orbiting one another. We keep the name Pluto for the larger one. The other, with over half its diameter, we call Charon. Charon is almost too large to qualify as a mere moon.

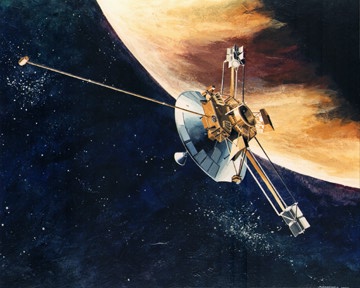

So far we've found nothing further from the sun than Pluto, but we recently put something there. We launched the small spacecraft Pioneer 10 in 1972. Its mission was to explore the Asteroid Belt and then fly past Jupiter. No one thought we'd still hear from it after a year or so. But NASA did etch images of a man and a woman on it and included a drawing of our location in the solar system -- just in case distant aliens ever found it.

Pioneer 10 made it through the asteroids without being hit. It sent back photos as it passed within 80,000 miles of Jupiter. It kept on going, and it kept on broadcasting. It passed the orbits of Saturn, Uranus, Neptune, and finally Pluto. Now it's seven billion miles away, and we can still make out its signal. It's far off in the cold of space -- twice as far from us as Pluto.

But Pluto is also in a cold place where the sun is only a distant star. Its temperature is 37 degrees Kelvin. That's over four hundred Fahrenheit degrees below zero. If it has any atmosphere, it's a thin vapor given off by methane ice. This is the last stop in our vast solar system -- unless you want to count Pioneer 10, which has now left the warmth of the sun entirely behind.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

For information on Pioneer 10, see: Wolverton, M., The Spacecraft That Will Not Die. Invention & Technology, Winter 2001, pp. 46-58.

I am grateful to Sherron Lux, UH Library, for suggesting this topic.

Image of Pioneer 10, courtesy of NASA